jdowning - 1-2-2007 at 03:55 PM

A happy, peaceful and healthy New Year to all.

One of my New Year resolutions is to pick up the threads of my oud restoration project that has been dormant for the past few months (see Restoration

of Egyptian Oud - part 1). Currently I am in the process of completing restoration of a mid 19th C keyboard instrument to playing condition for a

local museum but as this work draws to a close, I shall be able to pay more attention to the oud - as the spirit takes me - as I have many other

interests and projects vying for priority. Never a dull moment!

To recap, the oud that I have - purchased in Cairo, so is likely Egyptian (?), may date from around the 1920's. It has had a hard life and is

currently in pretty rough condition having been damaged and subject to past repairs - some of dubious quality. It is likely not in its original state

- the belly, for example, being a possible later addition and the neck having been shortened by about 4 mm.

My objective is, to the best of my ability as a craftsman, to restore (and preserve) this instrument to playing condition but in doing so, to make the

absolute minimal structural and material changes to the instrument - as it now stands - to achieve this objective. My repairs - like the repairs of

others before me - will become part of the history of this instrument.

I also hope that the details that I shall provide as work progresses might in some small way add to the common data base regarding the historical

structure of the oud.

As work proceeds I welcome any comments and suggestions from all those interested. Lets make this a project for the oud community as well!

So - down to action!

Today I began work on the pegbox - no particular reason why - I just felt like it. The pegbox is in poor condition and is partially detached from the

neck. The pegs are a motly collection of different styles and poorly fitting - however, I shall deal with the pegs later as a separate issue.

The partial detachment of the pegbox has caused flexing and splitting of the pegbox backplate. Repairs had been in the past by regluing the crack and

by a (failed!) attempt to secure the pegbox by pouring glue into the cavity below the nut.

Fortunately, hide glue had been used to effect these "repairs" so the poured glue was softened by moistening with water overnight and then scraped

out. This action also softened the glue in the repaired crack in the backplate which then 'opened up'. Removing the pegbox from the neck - using a

hair drier for heat - proved to be impossible. I could have used a fine razor saw to cut this joint but decided to cut the pegbox backplate instead -

as I figured that it would be best to replace this anyway.

Having removed the pegbox in this manner it can be seen that the pegbox itself does not have an integral end block but is seated directly into a

rebate in the neck - hence the difficulties in removing the pegbox and making repairs! This would seem to be a weakness in the original structure?

Note the marks made by a file or rasp at the glue joint - presumably in an attempt to increase the glue joint area for strength?

Is this method of joining the pegbox to neck a feature of traditional oud construction?

Here are some images of the pegbox prior to removal.

jdowning - 1-2-2007 at 04:04 PM

...... and here are some images of the pegbox joint after removal but before clean up.

Hosam - 1-2-2007 at 05:07 PM

Hello jdowning, glad that you resumed working on this project. Looking forward to follow your progress. Good Luck!

Dr. Oud - 1-3-2007 at 08:39 AM

I have not seen an oud peg box attached in this way. Another weak feature is how the backplate seems to stop at the neck's outer profile. Usually the

backplate extends into the notch which would make a much stronger joint. I would replace the back plate with one that continues to the full depth of

the notch. Whether you use a separate block in the pegbox or utalize the notched flange in the neck shouldn't make any structural difference, although

it looks harder to fit, and so possibly further weakening the pegbox. A separate end block allows you to clamp the side walls snugly, then overlap the

backplate, making the pegbox more robust.

jdowning - 1-3-2007 at 10:54 AM

Thanks for your commments and suggestions Richard.

Here are another couple of closeup images showing the pegbox mounting arrangement in the neck. As you can see from the end grain direction and

continuity there is no doubt that there never was a separate end block for the pegbox. The pegbox backplate did extend part way into the notch but as

there was so much residual glue in that area, I was unable to release that last part of the joint so decided to cut it free in order to preserve the

inlay on the back of the neck from possible damage at the joint. The remains of this bit of the backplate - which can be seen in the picture - will be

cleaned out later.

It does seem to be an unusual and somewhat complicated way to fit a pegbox. Nevertheless, in keeping with my objective to retain as much of the

original structure of the instrument as possible I shall attempt to repair the notch and refit the pegbox as it was before.

jdowning - 1-5-2007 at 03:16 PM

I have now cleaned out the pegbox notch in the neck - removing the remains of glue residues and wood fragments using hot water and a fine spatula - so

can now better assess the situation prior to repair.

The neck of this oud appears to be made from pine or similar resinous softwood with the pegbox glued to an integral, wedge shaped block (which forms

part of the notch into which the pegbox fits - apparently an unusual detail of oud construction). At some time in the past, the oud appears to have

been subject to significant damage resulting in a split neck block at one end and the neck being forced backwards resulting in splitting of the pegbox

mounting block (if we can call it that) and partial separation of the pegbox to neck joint. A past, unsuccessful, repair attempt to secure this

joint,by simply pouring glue into the pegbox cavity below the nut, is in evidence.

Unfortunately, the previous separation of the pegbox to neck joint has resulted in significant splintering of the pegbox mounting block which will

entail cutting away and patching a good portion of what remains in order to reach sound material if I stick to my original plan. I have, therefore,

decided to cut away the remains of this block entirely, fit a spruce end block to the pegbox and instal the repaired pegbox to the notch in the neck

as an integral unit in the usual manner.

Before proceeding with that, I need to plan work required for refitting the pegs which might best be done with the pegbox still detached. I have the

choice of making and fitting a new set of boxwood pegs with slightly oversized shanks and with heads made in the fashion of the originals or to

'recycle' the existing mixed set - reshaping the heads of the mismatched pegs, cutting a new taper on the shanks and plugging and re- reaming the

existing pegbox holes to fit. At present I prefer the latter course of action as I will preserve the original pegs - despite all of their

imperfections - but I have yet to measure the shanks of each of the old pegs to determine if recutting to a consistent 'standard' taper is feasible. I

plan to check that out tomorrow.

jdowning - 1-11-2007 at 12:53 PM

The question of the mixture of pegs and variable sizes of the peg heads on this oud was discussed in an earlier thread "Oud Pegs - Another Question"

posted in September last year. It concluded that generally all ouds are fitted with pegs of equal peg head size with the shanks protruding an equal

distance from the side of the pegbox.

The pegs in my oud are a mixture of a number of styles and different sizes of heads. Furthermore they are all cut with different tapered shanks and

the pegholes in the pegbox are also cut to different tapers - not necessarily matching the taper of the pegs.

The top image shows the different peg styles. The two similar pegs on the left - one with large head the other small and with the face of the pegheads

shaped concave - are in the majority so may be the original style (?). The central peg shown is an odd violin style peg and the two pegs on the right

of simlar style - have large and small heads but with the peghead faces shaped convex.

The bottom image shows the now splintered holes cut in the pegbox.

jdowning - 1-11-2007 at 01:20 PM

While it would not be a problem for me to make up a new set of oversized boxwood pegs for the oud, I am trying to preserve as much of the original

instrument as possible consistent with restoring the instrument to playing condition. I plan, therefore, to reshape the heads of the "mismatching"

pegs so that I end up with a set of pegs of the same style and to rearrange the location of the pegs in the pegbox so that the peg head sizes run

consistently from large at the nut to small at the 'tail end' of the pegbox. The peg shanks will be cut to a standard taper. The peg holes in the

pegbox are to be opened up in diameter to eliminate any splintered areas and the holes filled with boxwood plugs glued in place. The pegbox will then

be redrilled and reamed and the pegs precisely fitted so that they work properly.

The following two images show the original arrangement of the pegs in the pegbox at the time the oud was purchased (upper image) and the rearrangement

proposed below. The upper image also indicates the taper of each peg measured using dial calipers. These measurements are approximate because the peg

diameters are not all completely circular due to unequal shrinkage across the wood grain over time. Recutting the peg shanks will eliminate this

fault.

The peg shanks are to be cut to a "standard" violin peg taper of about 1:30 nominal taper. The reshaping of the shank will reduce peg shank diameters

a little from the original size which will be beneficial for tuning.

The pegs will finally have the original black stained finish restored.

jdowning - 1-11-2007 at 07:42 PM

Now to talk a bit about the tools needed for this work. This will be common knowledge to luthiers - amateur or professional - but I thought that the

information might be of interest to those less familiar with the details of how these instruments are made.

The shanks of the wooden tuning pegs of ouds, lutes, and other stringed instruments such as violins, are tapered to fit a hole of matching taper in

the pegbox. This arrangement provides sufficient friction for the peg to resist string tension yet operate smoothly (if correctly fitted) when tuning.

It is an arrangement that also automatically takes up any wear between the peg shank and peghole.

The tool for cutting the peghole is called a peghole reamer and these can be purchased from luthier suppliers as violin peg reamers - with a cutter

length of about 135 mm, small end diameter of about 9.5 mm tapering to about 5.5 mm that is with a nominal taper of 1:30 - for about $35 to $100

dependent upon quality.

I have experimented with other forms of tapered reamers - mainly morse taper engineering reamers that can often be found cheaply at flea markets.

These reamers have six equaly spaced cutters that tend to "chatter" leaving a less than perfect hole. They also have a shallower taper than a violin

reamer that is less satisfactory - the pegs tending to wear more quickly. A standard violin reamer (on the right hand side of the attached image) has

only three cutters set only on one half of the diameter - the rest of the reamer being solid. This arrangement allows for a smoother, more accurate

cut.

The image shows the cutter arrangement of a violin peg reamer and engineering morse taper reamer for comparison.

jdowning - 1-11-2007 at 07:54 PM

....... and here are some of my peg reamers (see previous post). The reamer on the right is a standard violin peg reamer and the one on the left is a

morse taper reamer that has been reground to a steeper taper (at a time when I had access to engineering toolroom facilities)- together with an

assortment of morse taper reamers picked up at flea markets for a few dollars.

If you have a metal turning lathe then it is a relatively simple matter to make your own smooth cutting reamers. Just machine some carbon steel 'drill

rod' to the required taper and then accurately file or mill the length to half its diameter. For occasional use in wood, this form of tapered reamer

does not even require hardening and tempering.

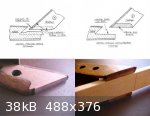

jdowning - 1-12-2007 at 06:49 AM

....... the attached images show the way in which a tapered steel blank- turned in a lathe - is hand filed to an exact semicircular cross section

along its full length. The completed reamer may then be hardened and tempered, if required, using a propane torch as a source of heat. The finished

flat must then be honed on an oil stone to produce a good cutting edge. As this form of reamer has only one cutting edge it cuts slowly but leaves a

well formed hole free of "chatter" marks.

Another home made reamer can be made entirely by hand without use of a lathe by filing a thin steel plate to the required taper and then gluing a

wooden backing plate to the steel with epoxy glue. The whole assembly is then carefully filed and sanded to an exact half round section - as indicated

in this sketch. I have not made a small reamer in this manner before but it should work as it is similar in construction to larger tapered reamers

used by woodwind instrument makers for boring out their pipes.

jdowning - 1-12-2007 at 02:59 PM

The other special tool required for making pegs is the peg shaper or shaver. This tool works like a giant pencil sharpener to shave a rough formed peg

shank to an exact taper - matching the taper of the reamer that is used to cut the peg holes.

Peg shapers are commercially available from luthier suppliers, ranging in cost between about $45 to $115 US. While these are no doubt tools of

excellent quality I have never used them, preferring to make my own shapers for a fraction of the cost (if I do not count the cost of my own labour!).

The advantage of making ones own shaper is that it is made with the peg reamer used to cut the peg holes - so that peg shank tapers will exactly fit

the taper of the peg holes. My violin peghole reamer is sold as having a nominal taper of 1:30 but in fact has a taper of 1:31.6 - which may not

exactly match the tapers of the commercial peg shapers. This can make a difference when it comes to accurately matching peg shank to peg hole.

Here are a couple of my home made peg cutters - made slightly differently but working on the same principle - simply made from a block of hardwood and

fitted with a rigid, cutting blade of suitable width. Not pretty to look at but they work. Rigidity and good fit of the blade to the body of the peg

shaper is important for smooth cutting action.

jdowning - 1-12-2007 at 03:51 PM

The following images show the stages in making a peg cutter. A block of hardwood (here I am using a piece of ash wood) is drilled through with a hole

of diameter equal to the minimum diameter of the peg reamer. The reamer is then used to cut the hole to a taper. The cut is made slowly, for accuracy,

and the reamer is frequently drawn from the hole to clear wood shavings clogging the reamer flutes as the cut is being made.

The wood above the completed reamed hole (shown as crosshatched in the photos) is then carefully planed down - using a hand plane - until the plane

just cuts through the top of the hole along its entire length. As the reamed hole is tapered this means that the top surface must be planed at a

slight angle to the horizontal. The bottom left hand image shows how the top of the block should appear after planing. The slot above the hole

provides clearance for shavings cut from the peg shanks when the peg shaper is in use. It is important that the planed surface should be absolutely

flat - to fit exactly with the cutting iron - and that the iron itself be absolutely rigid - otherwise it will "chatter" and not cut smoothly. As can

be seen from the images, I use heavy bolts to clamp the cutters in place and with an additional block of wood over the cutter to improve rigidity.

The cutting iron should be set with the cutting edge just protruding into the slot above the reamed hole so that it just takes a fine cut from the peg

shank as it is inserted into the peg cutter and rotated. A few trial and error cuts will find the best blade position.

The cutter, of course, must be sharpened and honed to razor sharpness. If it will shave the hairs from the back of your hand then it is sharp

enough.

There are a range of possibilities for the cutters. I use old plane irons and cutters from woodworking jointer machines purchased at flea markets for

a few dollars. The old fashioned plane irons from wooden planes are very rigid and made from laminated steel. The cutters from Makita hand planers are

also good as they are also of laminated construction with a high speed steel cutting edge, over 3 inches wide and thick.

I hope that these images and descriptions are clear enough but if anyone has any questions for clarification don't be afraid to ask.

Hosam - 1-12-2007 at 05:55 PM

Very interesting, thanks for sharing this with us.

jdowning - 1-13-2007 at 07:24 AM

Ooops!

The measured peg shank tapers previously posted on the 11 January were incorrectly calculated by me. The correct values range between 1:17 and 1:37

that is with the angles of taper ranging between about 3.3 degrees and 1.5 degrees. I have, therefore, edited the images posted on the 11th January to

reflect the correct figures.

Hope that I have got it right this time. Apologies for any confusion this may have caused.

Peyman - 1-13-2007 at 07:28 AM

Thanks for posting the pegshaver tutorial. Very useful.

jdowning - 1-13-2007 at 03:16 PM

Having checked the variation in peg shank taper and maximum shank diameter, I selected one of my peg shapers that is pretty close to the size

required, therefore, saving having to make up a custom peg shaper for this job. The first part of the work is to re-cut the peg shanks to close to the

final taper.

The cutter blade must be checked for sharpness. I always regularly hone the blades of all cutting tools that I use - between sharpening on an oil

stone - in order to maintain optimum sharpness. The peg shaper cutting blade, initially, must be lapped and sharpened absolutely flat on the back face

with the cutting edge sharpened straight over its full length (otherwise the peg shank taper will be curved along its length). I hone the blades on a

leather strop (hard leather glued to a flat wooden block) treated with a fine honing compound - I prefer the 'Veritas' blade honing compound sold by

Lee Valley (catalogue number 05M08.01) which cuts fast and leaves a razor sharp edge.

Setting the blade on the shaper is fairly critical as it must be adjusted to take the finest possible cut to avoid tearing the wood grain of the peg.

However, this is easily done by first leaving the blade lightly bolted to the peg shaper, inserting a peg to be cut and rotating the peg (towards the

cutting edge). If the blade is set too 'heavily' the peg will automatically push it back until fine shavings are starting to be produced. At this

point the blade is bolted tightly in place. Note that the edge of the blade is also set at a slight angle following the taper of the peg. After a peg

has been cut with this approximate setting for about 60% of its length. The blade is then loosened and reset as before but this time checking that the

fine shavings are being produced evenly along the full length of the cut.

Note that the entrance to the hole in the peg shaper is countersunk - made in the shape of a funnel - so that at the end of the cut the decorative

collar under the peg head is protected from accidental damage by the cutter. Note also that the leading edge corner of the cutter is lightly dressed

to an angle for the same reason.

The objective at this point is to cut the peg shanks close to the finished taper but that the final finishing operation - prior to later fitting the

pegs to the pegbox - will be to burnish the shanks - that is compress the cut fibres of the wood - to a more dense, polished surface.

jdowning - 1-13-2007 at 04:20 PM

Preliminary re- cutting the shanks of the pegs with the peg shaper is a fairly quick operation.

The shaper size used was not quite sufficient to remove all of the irregularities of the original pegs - there are still a few 'flat spots' remaining

on some of the pegs - but is close enough for this part of the operation.

The cutting operation revealed the wood from which the pegs are made - not the best quality unfortunately. Those pegs that I believe may be original

to the pegbox - pegs number 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11 - all seem to be made from a species of Beech wood, judging from the 'flecked' wood grain. (Peg

number 11 is made from a darker coloured wood, however). The sides of the peg box are made from two layers of wood - the outside being walnut and the

wood of the inside surface having a similar grain pattern to that of the pegs.

The other four pegs have a different style of peg head - Number 7 and 8 are made from a type of boxwood, and numbers 1 and 12 again from a kind of

Beech wood.

Beech wood is not a good wood for pegs - it is too soft and will wear quickly. True boxwood is good. Nevertheless, I shall continue with what I have

in the 'original' pegs.

Here is an image of some of the re-cut pegs.

The next stage will be to re-shape the peg heads to match.

Thank you for your interest everybody.

jdowning - 1-17-2007 at 01:50 PM

The reshaping of the 'mismatched' pegheads ( pegs #1 ,5, 7, 8 and 12) is in progress. The objective here is to reshape the peg heads from a convex

face to concave, matching - as closely as possible - the shape of the original (?) pegs - # 2, 3, 4, 6, 9 10, 11.

To produce the concave surface, I used a rubber drum sander 11/2 inches (38 mm) in diameter which matches the curvature of the original pegheads. The

sander was mounted in a drill press and each peghead held against the rotating sander, frequently checking progress of material removal to ensure that

everything remained square and symmetrical. The sander was also used to roughly round off the edges of each peghead prior to final shaping - which was

done with needle files and fine sandpaper.

Two pegs - # 7 and 8 - had a solid decorative collar below the peghead. These were grooved by hand to match the collars of the original pegs. This

operation was accomplished by holding each peg in a block of wood (drilled with a suitable sized hole and tapered with a peg reamer), using a fine

razor saw to produce a shallow cut which, in turn, helped to guide a knife edged 'needle' file to cut the groove. The peg was rotated in the holder

during the filing operation.

The attached images show the low cost drum sander used to shape the pegheads.

The bottom left image shows pegs # 1 and 5 after rough shaping. Note the flecked grain of the wood revealed by the drum sanding operation judged to be

Beech wood but may be another species - common to Middle Eastern countries - that I am unfamiliar with.

The bottom right image shows reshaped, and almost finished, peg # 7 against original peg #6 for comparison (these are the two smallest pegs in the

set. These seem to be made from a soft species of boxwood.

jdowning - 1-17-2007 at 02:37 PM

... note, for purposes of comparison - before and after - the image of the pegs posted previously on 14th Jan shows peg number 7 (first on left), peg

number 12 (fifth from left), peg number 1 (sixth from left) and peg number 8 (seventh from the left)

jdowning - 1-22-2007 at 01:46 PM

Before moving on to plug, re-drill and re-cut the peg holes it will be necessary to instal the new integral pegbox endblock in order to stabilise the

pegbox as a unit. The original mounting arrangement for the pegbox in the neck is represented in the top left hand sketch. Due to the amount of damage

and splitting of the original mounting block it has been decided to remove the block entirely and, alternatively, provide an end block integral with

the pegbox - as shown in the top right hand sketch. This - as Richard pointed out earlier in this thread - provides a stronger and easier to

instal/maintain arrangement. It also allows me to undertake the peg installation work with the pegbox detached from the neck - for convenience. The

original mounting block is less than 3/16 inch deep and is tapered - to provide a snug glue joint in the original assembly.

The inner cheeks of the pegbox were cleaned up to remove old wood rasp marks and old glue. Seatings for the new end block were then prepared by filing

(bottom left image). The new end block is made from sitka spruce (to match the softwood material of the original mounting block) - with grain cut on

the quarter - and is made 1/4 inch thick for added strength. The bottom right hand image shows the end block blank in place before, gluing and

trimming to size. (the untrimmed blank is made much longer than required in order to provide sufficient length required to facilitate accurate hand

planing and fitting of the tapered end block to the pegbox).

Part of the split pegbox backplate were cut away to provide clear access for the above operations. The split section of the backplate will eventually

be completely cut away and replaced with sound material - preserving as much of the original mahogany backplate as possible. As it will be impossible

to exactly match the grain of the original backplate, I plan to later splice in a new section of contrasting walnut wood.

jdowning - 1-28-2007 at 01:28 PM

One problem with living in Northern climates is that the relative humidity of the air can drop to quite low levels in winter - becoming as dry as the

Sahara Desert inside heated buildings.

I planned to glue the pegbox end block in my kitchen two days ago, this being the warmest room in the house which is heated with a woodstove.

Unfortunately, I left the peg box in the kitchen overnight when the temperature outside dropped to minus 25 Centigrade. Under these conditions, the

relative humidity in the kitchen dropped into the low 40's per cent and a split in the pegbox backplate appeared. This was probably just a hairline

crack opening up in the section of the backplate that I intended to cut out and replace anyway. There are repaired splits in the backplate visible on

either side of this crack - damage caused by the pegbox being subject to considerable backwards force some time in the past.

I have decided, therefore, not to cut out this damaged section of the backplate and splice in a new section but to completely replace the backplate.

The original backplate is mahogany but I do not have any true mahogany in my stock of woods but I do have quite a lot of walnut that is at least 100

years old so will make the new backplate from this material instead (the bowl of the oud is made from mahogany and walnut so this material

substitution is acceptable).

Just for information - I also occasionally restore and repair

19th C keyboard instruments so have quite a collection of parts and casings collected from instruments that are otherwise beyond repair (I never throw

out any wood until it has reached the stage of being good only for lighting the woodstove - nothing is wasted!). Most of these instruments have been

made from walnut which is a very useful source for repair work.

The attached images show the cracked backplate and the walnut backplate blanks that I have cut on a bandsaw. These will be allowed to dry out in the

house for a few days before use.

jdowning - 1-28-2007 at 02:38 PM

....... in the meantime I have prepared the plugs required for plugging , redrilling and reaming of new peg holes in the pegbox. The plugs are made

from old boxwood that I purchase for lute peg making over 30 years ago - a stock of spindle turning blanks that had been stored in a warehouse for

many decades before then - so should be well seasoned by now! Boxwood is hard and fine grained so should wear well in this application.

I have cut the plugs using a 3/8 inch tapered plug cutter manufactured and sold by Lee Valley (cat# 05J05.02 "Snug-Plug" cutter). The taper of the

plugs happens to match the taper of the standard violin peg reamer that I use and also matches the diameter of the reamer. I shall be using the peg

reamer to cut the holes for the plugs.

When cutting the plugs from the boxwood blank the operation must be done in a drill press, at low speed with the blank firmly clamped to the drill

table. The cutter is set so that it does not quite cut through the blank. The plugs are then freed from the blank by sawing away the remaining

material, at the back of the blank, in a band saw. Otherwise, if the plug cutter is allowed to cut right through the plank each plug then will jam in

the cutter and must be individually driven out by hand.

The advantage of using a plug cutter is that the wood grain of the plug can be made to align with the grain of the sides of the pegbox. The plug

diameters are all of equal size and a little larger than the peg shanks, so will become a decorative feature of the pegbox once complete.

jdowning - 2-1-2007 at 02:42 PM

My intent is to pre-drill the plugs before gluing them into place in the pegbox and reaming to size. This will avoid having to re-drill the pegbox and

will ensure the original alignment of the pegs is maintained. In fact these will be more like peg bushings rather than pegbox plugs. As I have not

tried to make and instal peg bushings before I decided to run some tests on the boxwood plugs already cut (i.e. on the side grain).

A plug holder was made by drilling a vertical hole through a block of wood in a drill press and then reaming the hole to the correct size and taper

with a peg reamer. Each plug to be drilled was simply pressed into the holder and the centre of the plug marked by eye. A pilot hole was then drilled

through the centre of the plug using a standard 3/16 inch diameter brad point wood drill. Each drilled plug was then knocked out of the holder with a

piece of wooden dowel.

The side grain plugs were found on test to be unsatisfactory as they all partially fragmented as the drill broke through the plug.

jdowning - 2-1-2007 at 03:24 PM

As plugs cut on the side grain will not work I then tested some plugs cut on the end grain. Slabs 1/2 inch thick were cut from the end of a block of

boxwood and plugs were cut in a drill press - as before - using the tapered plug cutter. For safety each block (measuring about 1 1/2 inches square)

was held securely during the cutting operation with 'vicegrip' locking pliers. Each plug was mounted in the plug holder, the centre marked by eye and

then drilled through with a 3/16 inch brad point drill. This time there was no fragmenting of the plugs and I was able to increase the diameter of the

pilot hole using standard metal cutting drill bits without problem. I then tried reaming out the drilled plugs (let's now call them bushings) to size

with each bushing held in the plug holder. This operation was successful and I was able to reduce the bushing wall thickness to under 1/32 inch or 0.8

mm without the bushings breaking in the process. Some of the test bushings were found to be bored a little off centre but this is minor fault that can

be improved with practice when making a batch of bushings. In practice, the bushings - bored to the minimum diameter of the peg reamer - will be glued

in place in the peg box before finally being reamed to size with the peg reamer.

The bottom images show the reamed test bushings in place on an unfinished peg - just for demonstration.

Jameel - 2-1-2007 at 04:02 PM

That seems like a very tedious way to bung the pegbox, j. I've used both side grain and end grain plugs, the latter simply being old pegs that I glued

in place them reamed. The problem here the grain direction. The pegs will sink in more because the grain in parallel with the peg's grain. It works

though. You would have a much easier time drilling if you plugged the holes in the pegbox first, then drilled and reamed. Break out is not a problem

if you drill carefully, and start with a small bit, so any breakout will be removed by the reamer. The absolute best way to plug old holes is to take

a heavy plane shaving of hard wood like box, saturate it with glue, and wrap it around a tapered rod of steel or other non-gluing material in a

spiral, insert into the hole until its tight, wait for the glue to dry then remove the rod, then ream. The hole is now made up of long grain fibers

all around the hole, this provides the best wear surface, since there are not areas of alternating grain (end merging to side grain) as in a typical

hole.

jdowning - 2-2-2007 at 06:52 AM

Thanks for your suggestions and comments Jameel. At this point in time I have just been testing the possibilities without committing to action yet -

so am still open minded. The production of the boxwood 'bushings' should not be so time consuming compared to the alternative of having to make dowels

and then hand cut them into tapered plugs using a peg shaper (I do not have any old pegs to use for plugs). The pre-drilling of the bushings is also a

fairly quick operation. I am convinced that the bushing procedure will work satisfactorily.

My main concerns with this method are that - because each bushing is tapered on the outside, they must all be inserted into holes reamed from the

outside faces of the pegbox inwards. This means that after installation each pair of bushings will have been inserted in opposite direction to each

other with their external tapers also running opposite to each other. However, the external tapers will guarantee a close fit (and good alignment) of

each bushing in the pegbox so I think that - once glued in place - it is unlikely that any will 'pop out' in use. I am more concerned about

undertaking a pegbox repair that may be non traditional - one that could be considered to be irreversible once the oversized holes for the bushings

have been cut.

The question of wear of the bushings may not be so much of an issue given that the refurbished pegs are all made from a softer material than the

boxwood of the bushings.

If I decide not to proceed with the use oversize bushings after all and revert to using tapered peg shanks as you suggest I would probably make them

from walnut to match the sides of the pegbox outer faces.

What do others think? Are there any ouds fitted with oversized peg bushings or collars - possibly made from bone or other hard material of contrasting

colour to the pegbox sides making them a decorative as well as functional feature? All comments welcomed.

jdowning - 2-20-2007 at 02:54 PM

Having just almost completed another non oud restoration project that has been waiting for 6 years for attention (or so my wife reminds me!), I can

now resume this thread.

I have decided to proceed with the pegbox bushing option as this - if it works, as I am confident that it will - may be a useful alternative repair

for future projects.

Today I prepared a batch of boxwood bushings using a 3/8 inch Lee Valley taper plug cutter. The bushings were pre drilled to minimum diameter of my

peg reamer.

The pegholes in the pegbox were reamed out to almost the maximum diameter of the peg reamer - first from one side then the other - keeping the reamer

aligned concentrically with the opposite peg hole throughout. Each bushing was precisely fitted to protrude a little on each side of the pegbox sides

- for trimming to size later.

Use of bushings helps to remove much of the damaged, splintered wood around the original pegholes.

jdowning - 2-20-2007 at 03:06 PM

The attached images show initial progress in fitting the bushings. The bushings protrude a little on each side ready for later trimming flush with the

sides of the pegbox but at this stage have not been glued in place.

To stabilise the pegbox assembly during the reaming operation the original damaged pegbox backplate (due to be replaced) remains in position (with

open cracks temporarily re-glued where necessary) and the new pegbox endblock - as yet untrimmed to final size - has been glued in place.

jdowning - 2-25-2007 at 10:08 AM

All of the boxwood bushings are now glued in place ready for trimming. As the bushings are cut on end grain, I first trimmed away excess material from

the bushings using a saw.

I first tried using a Japanese style flush cutting saw (used on the pull stroke) which has the teeth set on one side only to prevent cutting the

pegbox sides (Lee Valley Tools cat# 05K34.01). This worked fairly well but tended to 'ride up' in the cut leaving more material to trim away with a

chisel than I wanted.

The remaining material was then cut away with a paring chisel (lapped perfectly flat on one side) until flush with the sides of the pegbox.

jdowning - 2-25-2007 at 10:24 AM

I then tried using an XActo razor saw with the metal backing strip removed. The saw blade is only 8 thousands of an inch thick with very fine teeth so

was used on the pull stroke. Masking tape was wrapped around one end as a temporary protective grip. Strips of masking tape were positioned on either

side of the bushing to be cut to protect the sides of the pegbox from being scratched by the saw teeth. This worked quite well leaving minimal

material to be pared away with the chisel.

Then the sides of the pegbox were filed (using a flat, medium cut machinists file) to remove most of the old scars, undulations and other

irregularities as a preliminary to final finishing later.

jdowning - 2-25-2007 at 10:42 AM

The bushings were not large enough in diameter to cover the original splintering around two of the pegholes so the remaining damage was filled with a

touch of glue mixed with the sawdust from filing the pegbox sides. The filler will dressed flush with the pegbox sides once the glue has fully

hardened.

This is the outside of the pegbox after filing.

The next stage will be to trim the bushings in side the pegbox. As the damaged pegbox backplate is to be replaced, the bushings will be trimmed once

the the old backplate has been removed allowing easier access.

Reaming of the bushings and fitting the pegs will be undertaken once the new backplate has been installed.

jdowning - 2-25-2007 at 03:36 PM

Moving on to prepare the new pegbox backplate.

The blank for the backplate has been cut from a piece of 19th C American walnut on my bandsaw - a 14 inch Rockwell Delta fitted with a 'Viking' 1/2

inch blade, 3 teeth per inch (Lee Valley Tools cat #02j04.93 - no I am not a shareholder, they just sell good quality product!). This is the only

power saw that I have in my workshop and is used for all of my woodworking projects. It is set up so that I can accurately cut veneer to less than 1mm

in thickness - up to 6 inches wide, if I want. One of the most important factors in setting up a bandsaw is correct blade tension. If blade tension is

too low the blade tends to bend backwards under pressure of the cut and will distort causing the blade to 'run out'. The blade tensioner on my bandsaw

is theoretically calibrated to handle up to a 3/4 inch wide blade but - at that setting - the tension is far too low (the wider the blade the higher

the tension required). I have found that with the blade tensioner set to maximum a quality 1/2 inch blade is just about the widest that the machine

can handle.

The blank shown in this image is hand planed on one face before sawing, and is just over 1/16 inch (1.5 mm) thick.

The saw marks are then removed by hand planing. I use a small block plane with an adjustable throat finely set. The blank is clamped first at one end

to a flat pine board, planed, and then reversed and planed in the other direction to complete the process. The blank is then finished with a cabinet

scraper to remove any planing marks and reduce the blank to the required thickness.

A cabinet scraper does not actually 'scrape' but planes a very fine shaving. In this type of scraper the blade is first ground and honed to a bevel -

like the blade of a hand plane. The edge of the sharpened blade is then burnished or polished with a hard steel rod. This turns the razor sharp edge

of the blade into a hook shape which is the shape required for the cabinet scraper to function efficiently.

Measuring the thickness of the completed blank I find that it measures only 50 thousands of an inch whereas the original measures 73 thousands of an

inch. So - I must repeat this operation and prepare another blank of the correct thickness. Not a problem - I do not make instruments for a living!

jdowning - 2-27-2007 at 12:59 PM

The old damaged pegbox backplate was removed by brushing hot water along the glue joint inside the pegbox and using a hot iron to soften the glue. The

surface of the backplate inside the pegbox had no varnish finish so the water quickly soaked into the joint. Transverse burn marks were in evidence on

the backplate.

With the backplate removed the interior of the pegbox was cleaned up, bushings smoothed over with a file and the new end block trimmed to size all in

preparation for final finishing.

All old glue was removed from the backplate glue joint with a stiff cabinet scraper blade. This also levelled any irregularities in the joint.

Removal of all of the old glue is an important part of preparing the joint.

The scraper blade is sharpened differently from the blade in a scraper plane. The edge is first filed straight and square and then honed on an oil

stone to produce sharp 90 degree edges on the blade. The two edges are then burnished over with a hardened steel rod - each to an angle of about 10

degrees - to form a hook shaped cutting edge. Correctly sharpened and prepared a scraper blade will shave off very fine shavings - cutting not

scraping.

The replacement walnut backplate blank is finish thicknessed slightly oversize to 0.078 inch and cut roughly trimmed in readiness for bending to

shape.

The original finish on the backplate was tested and appears to be spirit based (shellack?) covered with a thick protective coating of a wax polish.

jdowning - 2-28-2007 at 10:07 AM

The new backplate will be hot bent, using a bending iron, to fit the curves of the pegbox. While I am at it, I shall also make a caul - hot bent from

1/4 inch thick plywood - for gluing the backplate to the pegbox.

For those interested in making their own lutherie tools here is my bending iron easily made from scrap material - not pretty to look at but it works,

has a wide range of heat adjustment and is versatile with large heat capacity. It is made from a piece of thick walled copper pipe that has been

pressed to an oval shaped section in a vice and bolted to an iron support bracket. Three layers of asbestos cloth have been used to insulate the

support bracket from the heat of the iron. A few spacing washers to create an air gap would probably work just as well.

A small propane torch has been mounted on the support bracket using a standard cable clip. This allows the position and direction of the flame to be

adjusted for heat control.

The bending iron could also be made from other materials such as steel or aluminium pipe.

As the heat source is a propane torch, this style of bending iron should only be used in the vertical position to avoid flame instability and danger

of 'flare ups' caused by burning liquid propane.

This bending iron is a heavy duty tool more than adequate for bending veneers a few millimeters thick but can just about handle plywood or other

thicker materials where a lot of heat capacity is required.

jdowning - 3-3-2007 at 01:53 PM

The walnut backplate and matching glue caul in 1/4 inch thick plywood have been bent to shape on the bending iron. Here they are being tested for

correct fit - a dry run before gluing - using some small fast action clamps picked up at the local dollar store (thank you China!). I shall need to

make a few minor adjustments for a perfect fit.

The backplate will be glued in place with hide glue. Hide glue is the most versatile of glues and should be used for instrument construction and

repair wherever possible. It is relatively cheap, non toxic, has an infinite shelf life in its dry granular form if stored properly, it can be strong

with short 'grab time' but can be diluted to vary strength and set time as required, it can be remelted with heat and humidity and it does not stain

wood. It is commonly available in two strengths a very strong brown coloured 'granular hide glue' with fast grab time and a purer, clearer 'pearl

hide' glue that is weaker with slower set time. I prefer to use the latter where appropriate.

The glue granules after being just covered in water and allowed to soak overnight are then heated and stirred to melt the glue using a water bath to

keep the temperature of the glue below 140 F. Above that temperature the glue will spoil.

When I attended general woodworking classes at school in the early 1950's we used only hide glue heated in cast iron, water jacketted, glue pots -

the pots being kept bubbling away all day so that glue was always ready when needed. I still have a couple of these that I keep as souvenirs of times

past. Today, I simply put the glue in a small clean glass jar - only as much as I need for the work in hand - and put the jar in a saucepan of boiling

water on the stove to melt the glue. I do not bother to check the glue temperature - I suppose that I should but life can get too unnecessarily

complicated. Once made up, the glue will not keep for more than a week so I just make up a fresh batch when needed and throw out the old stuff.

jdowning - 4-16-2007 at 09:05 AM

The new pegbox backplate has been glued in place and trimmed ready for shellacking. Before gluing, the end grain of the new pebox end block was sealed

by coating with hot glue and immediately searing the glue in place with a hot iron. I decided not to use the plywood glue caul as I was not able to

work quickly enough during the gluing operation. Instead I worked my way along the backplate reheating the glue with a hot iron and clamping as work

progressed.

I prepared the shellack by covering orange shellack flakes with about three times their volume of methyl alcohol in a 'mason' jar with a sealed lid

(to prevent evaporation of the fluid). This mixture was allowed to stand for two or three days until all of the flakes had dissolved. The white

sediment (impurities) at the bottom of the jar was discarded by decanting the clear shellac through a cloth filter.

The orange coloured shellack is good for coating dark woods and providing an 'antique' finish that hopefully will match the original finish of the

oud. The shellack is used very dilute so can be applied with a brush but many coats will be required - I am in no hurry! Normally, brush application

of coloured varnishes is difficult and requires a lot of experience to achieve a consistent finish. Using the orange shellack at high dilution -

although fast drying - avoids this difficulty. I will apply one coat each day - to ensure each coat is fully dried - with very light sanding between

each coat - sufficient only to remove any dust particles or other imperfections.

Once the shellacking is complete I shall fit the pegs. The original pegs have been refinished with a penetrating black stain. In common with other

luthiers like Jameel and Richard I prefer to use India ink - readily available from office supply stores. This ink is made from lamp black which

provides a dense opaque finish unlike stains made from analine dyes that tend to be translucent and show the wood grain. The peg heads will be further

sealed with a shellack coating.

Both the shellacking and peg fitting operations will be carried out with the pegbox detached from the oud for convenience and ease of handling.

Ronny Andersson - 6-21-2007 at 01:53 AM

John any update on the project?

jdowning - 6-21-2007 at 01:31 PM

Hi Ronny- thanks for your interest.

To update everyone, the project is still very much alive with the pegbox undergoing many coatings of shellac and the pegs stained and ready to be

burnished and fitted. More on this later. I shall split the rest of the work into two more sections - the soundboard and the body - so that I might

carry out the operations in parallel and keep everything manageable (I only have a dial up connection so uploading data can get very slow)

Among other things, I am currently very much involved with local museum projects - restoration work, demonstrations, historical displays etc. - so I

have to spread my 'spare' time in retirement accordingly. I also have two lute recital/talks scheduled for this summer season and have had to switch

priorities to rebuilding one of my lutes (and refurbishing its fitted case) for use in these events. This work is now almost complete but I had hoped

to have finished work on the oud as well because I plan to incorporate this instrument in my talk which deals in part with the history of the lute and

its music. As things now stand I shall likely still make use of the oud even in its partly restored state.

Regards

John

jdowning - 7-26-2007 at 02:13 PM

The final stage in this part of the restoration is the fitting of the pegs. This was done with the pegbox still detached from the neck for

convenience.

Using a violin peg reamer the bushings were carefully reamed out to size - ensuring that the reamer was kept in true alignment with both bushing

holes.

In this case the reamed hole at the tail end of the peg was found to be slightly oversize (possibly due to the way the blade of the peg cutter was

set) - but this is what I want anyway. The objective here is to make the fit of the peg at the peg head end slightly tighter than at the tail end of

the peg in order to minimise any twisting force along the peg shank that could cause destructive damage to the peg. The best fit is judged from the

markings in the bores of the bushings (left by the staining of the peg) which should be heavier at the peghead side than at the tail of the peg. The

refurbished original pegs - of rather poor quality - are of softer material than the pegbox, so will bed in faster. To achieve this fit the peg holes

were reamed until the peg had entered the bushing at the narrow end about half way and then the burnished section (the shiny bit) at the peg head end

was - little by little - carefully reduced by rubbing with a strip of fine emery cloth until the best fit was achieved.

Once all pegs have been fully 'bedded in', the pegs will be finally trimmed evenly at the tail end and the cut surfaces restained.

One of the pegs at the tail end of the pegbox was found to have been previously damaged by twisting of the wood fibres. This was repaired with a

couple of drops of "super glue" that were allowed to soak into the damaged area consolidating the fibres and bringing the peg back to full strength.

jdowning - 7-26-2007 at 02:33 PM

I should mention that the reaming of the pegholes should take place after the sides of the pegbox have been varnished as the varnish that soaks into

the bores of the bushings is then removed during the reaming operation.

I shall probably need to drill some new string holes in the pegs where the original holes no longer fit.

SamirCanada - 10-30-2007 at 10:51 AM

Any updates Sir John?