| Pages:

1

2 |

jdowning - 11-9-2008 at 01:43 PM

Thin and flat, (under 1.5 mm thickness) lute ribs, when bent to shape on a lute bowl mold, will take up a natural, shallow curve, or 'fluting' in

cross section. This is due to the transverse and longitudinal stresses in the bent rib coming into an equilibrium, or balance, state. This feature may

be less pronounced in ribs made from thicker material - as might be found in modern oud construction.

The attached image shows the fluted rib effect represented in a late 16th C representation of a lute (c. 1595) by Caravagio in the Hermitage

museum.

suz_i_dil - 11-9-2008 at 03:19 PM

If you didn't see it, there is a picture of a bowl like this on the forum, on a Tayyar oud.

And thank you for your explanation, I was thinking they had carved the wood...

But by this fact the bowl become not regular too, is this not of a bad incidence on the sound?

jdowning - 11-10-2008 at 06:52 AM

Thankyou suz_i_dil. I have not seen the picture of the Yayyar oud but will look it up. This subject of fluted ribs has been discussed at some length

on the forum (see the topics "Awsome Oud ribs" on the Projects Forum and "Oud with fluted ribs" on the Ouds,Ouds, Ouds forum). However, I want to

start this investigation afresh with a 'clean sheet of paper' and as few as possible preformed ideas - just to see where it might lead.

My objective in this topic is to investigate how far and by what method wood can be bent and formed into deeply fluted ribs without resorting to

carving. As this is a hands on experiment I have no idea, at this point in time, how these experiments will turn out but - success or failure - it

should be a useful learning experience.

Deeply fluted ribs can be found on surviving guitars, vihuelas and small descant lutes (mandolinos) dating from around the end of the 16th C. On these

instruments, the fluting may created by bending thin ribs or by carving thick ribs after bending. The attached image shows a section of carved fluted

ribs on an elaborately decorated early 17th C vaulted back guitar by Magno Stegher dated 1621 (Charles van Raalte Collection, Dean Castle, Kilmarnock,

Scotland). Typically, the body of the instrument is made from many, narrow ribs measuring about

7 mm maximum width.

Fluted ribs, formed by bending, may be found on two, well known, surviving instruments - a guitar by Belchior Dias, dated 1581, in the Royal College

of Music, London and a vihuela cat. E7048 in the Cite de la Musique museum in Paris. (There is some dispute about the designation of these instruments

as guitars or vihuelas but these arguments are irrelevant to this investigation). The attached image shows a section through the central rib of the

Dias guitar drawn to scale having a radius of the fluting about 18 mm and a reverse curve longitudinally having a radius of about 33 inches (838

mm).

This is a shallow longitudinal curve compared to an oud or lute rib, however, the guitar/vihuela ribs have sides that are relatively parallel whereas

lute and oud ribs taper sharply longitudinally. This sharp taper might make it possible to form fluted oud and lute ribs by bending alone although I

am not aware of any surviving early lutes or ouds that have this feature

The current wisdom, however, is that deeply fluted oud or lute ribs can only be made by carving and there are examples of modern luthiers making

instruments in this manner.

jdowning - 11-10-2008 at 07:22 AM

The great advantage of deeply fluted bent ribs is that the ribs may be made very thin (less than 1.5 mm) so the body of the instrument will be very

light but, at the same time, very strong and stiff due to the fluting. It has also been suggested that the fluting, in minimising contact with the

player's body, might improve resonance and sound projection of the instrument.

The following luthiers have made successful copies of the Dias and E7048 guitar/vihuelas so have developed a method for bending the ribs - although I

am not aware of the methods used in each case or if any of these was the method used originally by Dias.

Two of the sites (Batov and Larson) also provide MP3 audio recordings of their vihuela copies so that the impressive sound quality and resonance of

these instruments may be judged.

http://www.lutesandguitars.co.uk/htm/cat12.htm

http://www.vihuelademano.com/

http://daniellarson.com/chambure.htm and

http://daniellarson.com/

and also Rob MacKillop's site at

http://www.songoftherose.co.uk/

This investigation will commence next with some experiments to establish a method for bending fluted ribs as found on the above original instruments.

If this step is successful, the investigation will then move on to explore the possibility of making fluted oud or lute ribs by bending alone.

suz_i_dil - 11-10-2008 at 01:46 PM

A bit technical for me, just let me wish good luck in your investigation.

Very interesting research, indeed all the oud I tried which were really sounding great to my ears were all very light instruments.

jdowning - 11-11-2008 at 12:20 PM

Thinness of the bowl seems to have been a feature of early ouds as it was for lutes according to Arabic/Persian accounts during the Mediaeval period

in Europe. The accounts do not state 'how thin is thin' except to record that the ribs were made thinner than the soundboard. This may imply a rib

thickness of under 2mm. This does not necessarily mean that early ouds had faceted bowl exteriors like the lute - they could still have been made like

modern ouds starting with relatively thick ribs that are then shaped to give a smooth rounded bowl exterior. If this was the case then the bowl might

then have been shaped on the interior as well - to produce a uniform thin wall thickness.

BTW, I was unable to locate a picture on the forum of a Yayyar oud with a fluted rib bowl - all of the images posted seem to be of ouds with a

conventional smooth rounded profile.

The first stage of this investigation will be to establish a method for bending and forming the "inverted saddle", fluted form of rib found on the

16th C vaulted back guitar/vihuela examples posted . The attached image is a sketch representing the required general shape of this type of rib.

Constraints to be applied in the investigation are:

- the method must be one that could possibly have been used by luthiers of the 16th C.

- the method must be a process that will not result in deterioration of the structure or physical properties of the wood. However, removal of some

residual materials from within the cell structure of the wood (extractives - waxes, resins, mineral salts etc.) may be acceptable if found to be

beneficial in improving bending properties.

- after bending, the geometry of the wood shall be fixed and permanent - within a reasonable tolerance (recognising that all wood expands and

contracts with humidity/temperature variation)

There are a number of possible bending procedures which may or may not work successfully. These are to be considered, tested and evaluated separately.

All methods will require the wood to be temporarily softened and/or made 'plastic and remain in that state long enough for the wood to be clamped to a

mold of required shape without splitting or breaking.

suz_i_dil - 11-12-2008 at 04:53 AM

Here is the pictures I was talking about :

http://www.mikeouds.com/messageboard/viewthread.php?tid=2686#pid290...

Hope it may help you in your research.

Regards

jdowning - 11-12-2008 at 06:17 AM

Thanks suz_i_dil. Those are nice examples of ouds with fluted ribs but the question is - is the fluting of the ribs created by carving the ribs after

assembly into a bowl or by bending prior to assembly? If they are carved - and I suspect that they are - then the inside of the oud bowl will be

'smooth'. In other words the bowls are conventional except for their carved outward appearance. This can easily be verified by viewing the interior of

the bowls through the soundholes (Samir?).

Luthier Foad Jihad (?) of Iraq makes similar oud bowls. The fluting of his ouds is confirmed to be achieved by carving not bending (see "Awsome Oud

Ribs" on the Oud Projects forum).

If a method can be found to successfully flute oud or lute ribs by bending, then another alternative might be not to flute a rib but to reverse the

direction of the transverse bend from a 'cupped' fluted section to an arch. A rib curved across its width in this manner might be used to efficiently

produce a conventional smooth surfaced oud bowl having very thin ribs of uniform thickness. Just a thought at this stage though.

A very useful and informative reference about wood, its structure, properties and commercial applications is available for free download from the U.S.

Forest Products Laboratory at

http://www.fpl.fs.fed.us/documnts/fplgtr/fplgtr113/fplgtr113.htm

This is the Wood Handbook, a publication dealing with wood as an engineering material but which can be selectively downloaded chapter by chapter if

the engineering applications are of no interest.

jdowning - 11-12-2008 at 01:20 PM

Wood is complex structurally but simply put, is comprised of longitudinal fibres which are hollow, tubular cells with the cell walls made of cellulose

compounds - a kind of sugar. The cells make it possible for transfer of nutrient containing sap within a tree. The cells are joined to each other with

'lignin'. Lignin, softens at temperatures above 170 C/ 340 F but in the presence of moisture, the softening temperature of lignin is lowered to below

the boiling point of water (100 C/212 F).

In a softened state, the wood cells may be compressed considerably but stretched very little before failing.

Lignin may also be temporarily softened with chemicals.

The objective of this first part of the experimental process is to try to get a general feel, quickly, for what bending procedures may or may not work

in practice. Samples of seasoned American walnut and Maple - quarter sawn - measuring about 35 mm wide by 135 mm long by 1.2 mm thick (1.375 X 5.30 X

1/16 inches) were prepared, planed smooth both sides.

A 'male' mold, (the type used by luthier Dan Larson), on which the test pieces will be formed - representing the geometry of the central rib of the

16th C Dias guitar - was cut from a piece of pine. The mold is about half the length of the Dias rib for preliminary test purposes - to save time and

material. This mold configuration is the easiest to manufacture - quickly made by cutting the longitudinal curve on a bandsaw and then shaping the

cross section with a rasp. The longitudinal curvature of the mold was made with a radius of 27 inches (656 mm) - tighter than that of the original

Dias rib (33 inches/ 838 mm), to allow for some anticipated 'spring back' of a bent rib after release from the mold. The longitudinal curvature was

accurately measured using a set of standard draughting curves.

The attached image shows the completed test mold. The nails in the side are convenient anchor points for the string that will be used to tie down the

sample to the mold

So - ready to go for the first test.

Peyman - 11-12-2008 at 04:18 PM

This is really interesting. I had no idea that's one way of making the fluted ribs. Looking forward to the experiments.

jdowning - 11-12-2008 at 05:33 PM

The first test was to heat dry, seasoned wood samples to above the softening temperature of lignin. This is the technique familiar to all luthiers -

it works very well in two dimensional bending using a heated bending iron where the curve of the flat rib may be induced - little by little - by

heating and cooling to permanently set the required curve.

On a much larger scale, this technique was used by Naval shipyards - in the days of wooden sailing ships - to bend massive timbers. The heavy timbers

of oak - up to 4 inches (100 mm) in thickness were buried in sand in a furnace heated to the required temperature and left for several hours. After

'soaking' at the required temperature, the timbers had attained sufficient flexibility so that they could be relatively easily bent into a required

curve. (It is very likely, these ship's timbers would have had a moisture content at or above the air dried saturation limit of about 20% which, in

turn would have helped to soften the wood for bending).

Thin rib blanks cool very quickly and so lose their flexibility (in a few seconds) when removed from a heat source. Using a convenient heat source

(hot air gun) it was found impossible to manipulate the test piece on the mold quickly enough without each test piece splitting in two. Two samples -

quarter sawn and flat sawn - both failed. Test failure #1!

For this method to work, the rib blank would have to be subject to a constant, uniform high temperature, forced into the contours of the mold by some

means and then allowed to cool. This might be achieved using an electric heat blanket and pressurised, heated molds or by heating the mold and rib

blank in an oven together with, say, an heated, flexible, heavy sand bag (or a string of metal weights) to provide the required forming pressure. As I

do not have an electric heating blanket (and neither did 16th C luthiers) the former option has been discounted. The latter option might work but is

too complicated for consideration right now. There must be an easier way?

jdowning - 11-12-2008 at 06:18 PM

Wood, when freshly cut and full of sap ('green' wood) - dependant upon the species, - may be soft and flexible enough to be formed to shape on a mold

where it will permanently attain (within limits) the shape of the mold on drying and seasoning. The disadvantage of this method is that it is slow and

the wood may be subject to cracks and splits during the drying process unless carefully controlled. Also, slab cut wood is less stable than quarter

sawn under variable humidity conditions.

For information and interest, here is an image of a sample of wood (vinewood) that was slab cut from a 2 inch (50 mm) stem earlier this year and

allowed to air dry. Note that the sample, on drying, has naturally attained (almost!) the ' inverted saddle shaped' geometric profile that is the

objective of these test - without using a mold!!

Also, this vinewood has no visible seasoning splits or cracks.

The reason that this sample has taken a fluted profile is because of the differential grain length across the slab cut section - shorter at the bottom

of the sample than at the top so that the shrinkage on drying is less at the bottom than on the top of the section (see the bottom two images of end

grain). The longer the grain length the greater the amount of shrinkage. Also, as the transverse stresses induced by this natural curvature must be

balanced by an equal and opposite stress, an opposing longitudinal curve can be seen in the sample.

This is test #2 which may have some useful future application.

Clayton - 11-12-2008 at 07:43 PM

Always fascinating and I love your scientific method of exploration... illustration, and documentation! I think that vinewood really has some

potential. I like the way it feels. This is a great thread... I love the look of the fluted lute back and might really be interesting on an Oud.

Keep up the good work.

-Clayton

jdowning - 11-13-2008 at 06:23 AM

Thanks for your interest Peyman and Clayton.

This exercise began a couple of weeks ago when searching for a method to soften wood - not in order to bend it - but to make it easier to slice across

end grain in preparation for microscopic examination of wood grain structure. A perfectly clean cut is required and most seasoned woods are too hard

and require softening. Freshly cut ('green') wood, on the other hand, may be cut cleanly without prior treatment as the structure is soft - the cells

being full of sap and the cell walls saturated with liquid matter.

A method used to soften dried wood samples is to boil them in water until the sample sinks - an indication that the cells of the sample are fully

waterlogged. At this point the sample has - in effect - been 'reconstituted' to its 'green' state (like adding water to dried food). The boiling of a

small sample may take up to an hour or more depending upon its porosity and density. Some wood species, however, are so hard that they require a

further softening treatment prior to boiling (see 'Identifying Wood' by Bruce Hoadley, Taunton Press). This may be accomplished by first soaking a

specimen in a 50/50 solution of alcohol and glycerine for several days.

Cutting of a sample must be done immediately after a sample has been removed from the boiling water.

Clearly, this treatment does not permanently modify the cell structure of the wood under examination and so is reversible.

Boiling or steaming wood at atmospheric pressure (temperature 100 C/ 212 F) is a well known method for softening wood prior to bending - used by boat

builders and furniture makers for example. In building wooden boat hulls, the softened planking may be subject to bending in three dimensions - curved

and twisted.

I have used this method in the past for bending replicas of 19th C wooden hay rakes and offset broad-axe handles - the heating chamber being simply a

one gallon metal can half filled with water with a piece of metal duct pipe stuck in the top. This device was placed vertically on a camping stove,

the water brought to a boil and the wood to be bent suspended in the 'steam pipe' until soft enough to bend. 'Speed is of the essence' here using a

prepared jig into which the softened wood must be quickly clamped before it has a chance to cool and reharden to a permanent bend.

Oud or lute ribs may also be bent by this method but - being so thin - tend to lose heat and reharden quickly.

Curious to find out if pre-soaking a sample of wood prior to boiling might delay the the hardening of boiled, plasticised wood I extended my search

further afield to find out if there might be fluids other than water and alcohol that could be tested as a pre-soak agent. Use of glycerine (a kind of

soap) is not under consideration here due to the possibilty that its presence in wood might adversely affect gluing properties.

Peyman - 11-13-2008 at 09:31 AM

I tried this method once with maple strips about 3 mm thick: I soaked them in water for 24 hrs, then used a heat gun to bend around a plywood form. It

worked very nicely. This method really didn't work for rosewood and walnut (might have had something to do with the grain). I now use an electric iron

(for ironing clothes).

I also read about a method called "cold bending." It's used with violins. They soak the strips for a week then bend them over a form and let dry.

Apparantly it works as I have read the same with some Persian instrument makers who soak in water and don't heat anything. The drying time is probably

long.

The other method that I read about is used in frame drums and banjo rims. The wood is soaked with Ammonia and that softens it. Then it's bent over a

form. I think it's probably not a good method for bending since ammonia is particularly nasty.

jdowning - 11-13-2008 at 01:05 PM

Thanks Peyman.

As Ammonia is already on my list of 'pre-soak' liquids to test lets start with that first. A modern commercial method used to temporarily plasticise

wood is to soak it in liquid ammonia. This apparently softens the lignin (without heat) to the point where the wood can be permanently formed into

extreme shapes not possible using conventional wood bending methods. However, as liquid ammonia boils at minus 33 C it must either be kept under

pressure in a vessel and/or refrigerated to keep it liquefied. Nevertheless, it may still be feasible to soak thin wood strips (fror the required

minute or two) in the ammonia liquid as it boils off at ambient conditions of temperature and pressure. This would have to be done in a laboratory

fume chamber where the ammonia gas given off could be safely conducted to atmosphere. By all accounts this process would likely work in producing the

desired fluted oud or lute ribs. It might be possible to obtain liquid ammonia from, say, a commercial refrigeration company but the stuff is way too

hazardous to mess around with for a back yard project and it is considered to be an environmental hazard to boot. Furthermore, as liquid ammonia was

not a material available to 16th C luthiers, its use is automatically discounted for the purposes of this investigation.

Household ammonia is a solution of ammonia gas in water - from 5% to 10% by weight - readily available, 'off the shelf' in local stores. However,

experts state that household ammonia is useless for plasticising wood - liquid ammonia must be used to be effective. Nevertheless, I have included

household ammonia on my list of liquids to test as some claim to have had success in using this product to reversibly soften wood.

Ammonia salts (for example sal-ammoniac or ammonium chloride, found in volcanic regions) have been known from very early times - known to Greeks and

Romans and mentioned in Arabic texts as early as the 8th C. Mixing sal-ammoniac with quicklime (prepared by roasting lime - a technology known to

earliest prehistoric man) produces ammonia gas. This was reported by the 15th C - but was probably earlier knowledge. So, it is likely safe to assume

that by the Mediaeval era in Europe, the equivalent of household ammonia would have been known and available.

Ammonia gas is also produced by the natural decomposition of excreted animal wastes so burying wood samples in a farm manure pile might be an

alternative possibility - but one that I am not ready to explore right now!

jdowning - 11-13-2008 at 01:33 PM

As alcohol has been mentioned as a wood softener, I have included white table wine on my list - around 15% ethyl alcohol by volume. Again, this would

have been a liquid available to early civilisations.

Also included is household white vinegar - sour wine - also available to the ancients.

In my search, I came across a reference where the engineers at JVC had discovered (after a search of 20 years) that after immersing panels of Birch

wood in Sake (Japanese rice wine) the wood became flexible enough to form into cones that they use for Hi-Fi loudspeakers. Distilled spirits of

alcohol apparently do not work (so forget about using a shot of Jack Daniels or single malt whiskey - thankfully!). Sake is more of a beer than wine

as it is subject to a double fermentation process - not using yeast to convert starch to alcohol in a single fermentation, as in the case of wine but

instead using the fungi Aspergillus oryzae - naturally present (like yeast) in the environment. Sake comes in various types - some with added alcohol

content - and the JVC engineers, understandably do not go into further detail but they reckon that it is the presence of this fungi strain in the Sake

that, somehow, does the trick.

With curiosity getting the better of me, I bought a bottle of cheap 'table' Sake from a local store (about 15 % by volume alcohol with no added

alcohol) for testing. Well, to be honest, I just wanted to sample the Sake as I have some doubts as to wether or not it will work!

Cheers! Salut! Disappointing, however, to find that the beverage is not to my taste.

jdowning - 11-13-2008 at 01:42 PM

So, if it really is the Aspergillus genus in sake and not the ethyl alcohol content that is responsible for softening the wood, I looked for

alternative fluids where active residues of the genus might be found. Soy sauce might be one. However, a pharmaceutical product by the trade name of

"Beano" - made from another strain of the genus Aspergillus terreus - readily available 'off the shelf' for those unfortunates with socially

unacceptable digestive problems, has been selected for testing - i.e without the alcohol content of Sake.

jdowning - 11-13-2008 at 02:53 PM

'Beano' (continued) - contains the enzyme, Beta-galactosidase (from the Aspergillus terreus fungus).it is reported that "the pulp and paper industry

benefit from the enzyme production capabilities of certain fungi to soften wood fibres - including lignin biodegradation". The enzymes break down the

cellulose (sugars) of the cell walls apparently. Don't ask me how - I am not a biochemist!

The solution strength that I have arbitrarily chosen to use for the tests is three 'Beano' tablets to 20 ml (cubic centimeters) of water.

The final choice of pre-soak fluid for these initial preliminary tests is Methanol or wood alcohol - again, readily available off the shelf. Methanol

(distilled from wood) was used by the Ancient Egyptians in the embalming process for mummification so was well known to early civilisations. I chose

this because it is a concentrated alcohol and - because it is derived from wood - which seems to be appropriate for these trials. All guesswork at

this point in time.

Methanol must be handled with plastic gloves in a well ventilated place as inhalation of the fumes and absorption of the fluid through the skin, can

prove to be dangerously toxic.

So - with my workshop now smelling faintly of a brewery, we can now move on to the next phase.

patheslip - 11-13-2008 at 03:20 PM

Late night disconnected thoughts:

Horrified to learn sake involves Aspergillus. This fungus can kill. I put some fallen leaves in plastic bags to encourage breakdown. When I opened

them I must have breathed in the spores. Ended up in hospital. Another gardener died from the same thing this year.

I shall avoid Japanese restaurants.

Returning to our moutons: fungus softens wood prior to digesting it. The change is permanent. Is this what you want?

Bending wood: I made a coracle from ash, heating the wood in a plastic drainpipe filled with steam from a modified pressure cooker. Very tricky

holding that hot wood and bending it into shape. How did the shipwrights do it with much bigger planks? Luckily for us ouds are measured in

millimetres not inches.

Good luck with the project

Peyman - 11-13-2008 at 04:20 PM

Interesting investigation with the materials.

Ammonia is definitely not a good idea.

What about using those veneer softeners? I didn't search how they work but is worth looking into, since the ribs are so thin.

jdowning - 11-14-2008 at 07:04 AM

Thanks for your constructive observations Peyman and patheslip.

The pre-soaking or 'marinating' of the wood samples began over a week ago and bending of the samples has begun. As I only have a single mold, bending

tests are sequential and are being completed at the rate of one per day. It will be a few days before this initial trial is complete so I shall post

the full findings then.

In the meantime I have started to reconsider the potential of using 'green' wood more seriously than earlier in this thread. Peyman has confirmed that

some luthiers, East and West, cold bend instrument ribs (presumably in a softened state) and allow the ribs to dry on a mold where they take up the

shape of the mold permanently. Green wood is used on instrument bowls that are carved from a solid block as the wood is softer and easier to carve.

The initial carving brings the wall thickness close to finished size and the bowl is allowed to slowly season and dry before being finished to final

dimensions. In general, most luthiers work with well seasoned wood in instrument construction to avoid all kinds of potential problems with wood

splitting etc. Nevertheless, if soft and flexible 'green' wood is used (unheated) in order to successfully conform to a complex three dimensional

shape - like a fluted rib - and then allowed to dry and fully season on a mold before being assembled into an instrument there should not be a

problem. Due to the thin wood sections being contemplated the natural seasoning period might be relatively short - a month or two perhaps. This would

potentially be a far more efficient procedure than working with fully seasoned rib blanks, softening them by some means and then trying to heat bend

them to shape. Heat bending particularly presents handling difficulties.

Some woods do bend easier than others which might have something to do with cell diameter and distribution. The large diameter early wood cells tend

be thin walled whereas the small late-wood cells are thick walled. So wood with a greater proportion of large diameter early wood cells might be

relatively easier to bend. Note the macro section of vinewood posted above. It is comprised mainly of large diameter cells and the wood is very

pliable even when cold and dry (see 'Wood Fit for a King' on this forum). Woods with small, widely distributed cells such as Beech are much stiffer

and harder to bend.

I have no experience with veneer softeners so don't know how they work but will check it out as a possibility.

The possibility of Aspergillus in Sake being the active ingredient for bending wood is just a quote from the JVC engineers. I doubt if there would be

any fungus residue remaining in the beverage - which is why I questioned if it is the alcohol that is the active ingredient. However, I wonder if the

action of the fungus during the fermentation process results in production of enzymes (as in the case of 'Beano') that do remain in the drink and are

an active constituent in softening the cell walls of the wood?

I think that partial softening of the wood cells by controlled immersion in a bacterial 'soup' might be an acceptable possibility. Immersion of

freshly felled logs in water to prevent splitting and insect attack (known as ponding) is standard practice in the logging industry. It has also been

found that action on the ponded logs by bacteria in the water can result in degradation of pit membranes in the cell walls allowing freer transfer of

fluids through the woods. Useful for wood that is to be chemically pressure treated but also with possibilties for impregnation of the wood with other

fluids - such as pre-soak fluids in our case.

All this has reminded me about another old method of preparing and using green wood - practiced by the North American Indians to make baskets from

Ash. The freshly felled Black or Swamp Ash tree section is first immersed in a stream (freshly felled Ash dries and end checks very quickly after

felling - within an hour in my experience). After remaining immersed for a time (not sure how long but can find out. Many days or weeks as I recall)

the log is taken from the water, the bark removed and the whole surface of the log pounded with wooden mallets. The pounding causes the wood fibres to

separate along the growth rings so that long, thin strips of the still soft wood may be peeled from the log. The process is repeated to remove

successive layers, gradually reducing the log diameter until too small to be used. The thin flexible wood strips (about an inch or so wide) are then

tightly woven into baskets (or chair seats ) and allowed to air dry and harden in place. The end grain direction in this case is across the width of

the strip (not quarter cut).

patheslip - 11-14-2008 at 09:31 AM

Your remarks about ponding bring to mind some other old country practices. Elm wood, from this once ubiquitous tree, was ponded to make it water

resistant. The large branches, which hollow naturally, were widely used for pipes and village and farm pumps and hollowed out pieces of trunk for

water troughs.

Withy branches are still ponded for basket making in those damp parts where the willow grows well. They're tied in bundles and laid in water for a

year and a day.

jdowning - 11-14-2008 at 11:57 AM

Checking out veneer softeners - one apparently effective home made softener is made by mixing 8 oz glycerine and 8 oz denatured alcohol in a gallon of

water. This is essentially the same as recommended by Hoadley for softening wood by pre-soaking mentioned in an earlier posting - except that it is a

50/50 mix without water added. I was incorrect in thinking that glycerine was a kind of soap - it is a kind of alcohol so should not have adverse

effect on gluing properties. Glycerine is derived from the soap making process as a byproduct left in the boiling vat after the soap has been skimmed

off. Apparently glycerine was not identified until the late 18th C which should disqualify it from consideration here. However, it is very possible

that the impure glycerine containing liquid could have been used in earlier times - it's just that it wasn't known as glycerine. The impure liquid

contains about 25% of common salt (sodium chloride) that at one time was crudely purified by repeated boiling in open vats, removing the salt that

crystallised on the sides - a simple process well within the capabilities of earlier civilizations.

So glycerine is back on the list of pre-soak possibilities.

jdowning - 11-15-2008 at 04:47 AM

I should mention that sale of denatured alcohol (for example ethyl alcohol with 10% methyl alcohol added to blind or kill anyone foolish enough to

drink the stuff), is restricted in Canada so is not an option for use in these tests. Methylated Spirits is (or used to be) readily available in the

U.K. and unrestricted - the same applies in the U.S.A. apparently.

jdowning - 11-15-2008 at 12:09 PM

With the pre-soaking tests in progress, preparations for the second phase of this investigation - to make full sized fluted oud or lute ribs - have

gone ahead with the making of the molds. I plan to test both male and female type molds into which the softened rib blanks will be clamped and allowed

to re-harden.

The profile of an early 17th C lute has been used for the molds. Both molds were straightforward to make. The male mold version was made from a piece

of elm wood with the rib profile cut out and the curve of the flute cut using a rounding over bit in a router. The female mold was a little more

complicated as it has to be made in two halves. Two pine boards were screwed together and cut to the required rib profile using a bandsaw. After

smoothing the profile, the two halves were separated and the inside curve of the flute cut with a coving cutter using a router. The two halves were

then screwed back together - the screws providing perfect registration and fit of the parts.

In my haste to make the molds, I forgot to provide extra height to the profile of the female mold to allow for the depth of the flute so this mold is

smaller than it should have been. Not to worry, this is only a mold designed to test the feasibility of making fluted ribs. If it works using this

mold - the method will also work for larger or smaller molds.

Additional nails or screws will be fitted to the male mold to provide anchor points for the string windings that will be used to provide the clamping

force on the rib. The clamping force on the female mold will be provided with a rope or fabric tape under tension or using a series of shaped wooden

blocks clamped in place. The method that works best under test will be the one chosen.

jdowning - 11-15-2008 at 12:35 PM

The rib blanks will be cut a little oversize to the required profile (to allow for final trimming) - ie tapering to a point at each end. This will be

necessary to minimise the stresses under tension generated along the outer edges of the rib when clamped in place. This is possible because the depth

of the flute diminishes from the centre of the rib to the extremities. Attempting to bend a parallel sided rib blank would be more likely to fail due

to the greater tensile stresses generated along the edges. If the methodology proves to be successful, most of the fluted shape will be achieved under

compressive stress loadings that the wood cells are able to tolerate much better than if subject to tensile loadings. At least, that is the theory -

the 'proof will be in the pudding'!

The images show rib blanks positioned on the molds as they would be prior to clamping in place following softening of seasoned wood (or when

'green').

jdowning - 11-16-2008 at 11:08 AM

As I have 'green' vinewood to hand that I know is very flexible it was decided to try to try to 'cold' bend a sample on the male mold. At the same

time, advantage was taken of the natural curvature in the vine stem selected. The stem was first cut longitudinally through the centre and then sliced

into curved strips, about 3 mm thick using a bandsaw and temporary wooden guide clamped to the bandsaw table.

The outermost strip was chosen for the test - this being slab sawn so that the grain would cause the strip to 'cup' in the direction of the flute

curavture on drying.

The strips were very flexible longitudinally and there was moisture (sap) visible on the cut surfaces.

jdowning - 11-16-2008 at 11:13 AM

The strip selected was so flexible that it could be flattened with the weight of a small plane. The top surface of the strip was, therefore, planed

smooth - this surface being in contact with the mold. The thickness of the strip was about 2mm after planing one side. The opposite side was left with

the sawn surface.

The strip was cut to the dimensions of a rib ready for clamping to the mold.

jdowning - 11-16-2008 at 11:48 AM

The rib was clamped to the mold using string wound tightly around the mold. A quick convenient method that applies a gradual increasing clamping force

as the string winding progresses. The rib blank readily conformed to the longitudinal curve of the mold but failed by cracking along the centre line

as loading was applied by the string. Clearly the combined transverse and longitudinal tensile stresses (with greatest stress along the centre line)

exceeded the tensile stress limit of the wood.

What can be learned from this failure? The vine rib blank was not clear and straight grained but contained knots and crooked grain. The cracking

initiated in the grain irregularities surrounding the knots. The rib blank measured 2.3 mm thick which is likely much too thick. The string winding

does not provide uniform support of the surfaces under tension. A series of metal (or woven fabric) bands for clamps might be a better arrangement for

providing even support.

For this procedure to have a chance of succeeding, a rib blank must be straight grained and free of flaws, thin (under 1.3 mm say), and be fully

supported during bending against tensile stress failure. It must also, of course be soft and flexible prior to bending.

It is uncertain at present if a blank should be quarter sawn or slab cut for best effect.

The initial pre-soaking trials of phase 1 of this investigation will be completed and reported on tomorrow.

jdowning - 11-17-2008 at 12:51 PM

Pre-soaking/ Boiling Bending Tests.

Test samples were prepared from Black Walnut and Maple, each, quarter sawn, measuring about 35 mm wide by 135 mm long by less than 1.5 mm thick -

planed smooth on both sides. The Walnut was wood recovered from a 19th C reed organ so has been drying for about 100 to 150 years. The Maple has been

drying for at least 30 years - but probably a lot longer than that - so both species are well seasoned.

The saddle shaped wooden mold previously posted has been made to the same rib shape as the 16th C Dias vaulted back guitar i.e. with longitudinal

curve measuring 27 inches radius (686 mm) and a flute radius of 18 mm (less than 3/4 inch). After soaking in the chosen marinade for several days,

each sample was boiled in fresh water for 5 minutes before being quickly clamped to the mold by binding it with string. The string binding method is

very simple and applies a gradually increasing clamping force. The main purpose of boiling was to cleanse the wood pores of any residual marinade and

to heat the wood in order to accelerate drying of the sample in the mold - although some softening of the wood, due to boiling, probably occurred as

well.

Each sample was left to dry, clamped to the the mold, in a warm room (at about 20 C/ 65 F, relative humidity about 65%) for 24 hours. After being

released from the mold each sample was allowed to dry for a further 24 hours before being measured dimensionally.

The first test, as a 'benchmark', was to try to bend a sample - without any pre-soaking - simply by boiling it in fresh water for 5 minutes. This

Walnut sample failed by splitting down the centre well before the string winding could be completed and full pressure applied. The test was not

repeated using a Maple sample as boiling alone, to soften the wood, is clearly not going to be an effective procedure for these tests.

jdowning - 11-17-2008 at 01:21 PM

The marinating of the samples was accomplished by placing a Walnut and Maple sample, together, in a small 'Ziploc' type plastic bag with about 15 to

20 ml (cubic centimetres) of the chosen marinating fluid. The bag with samples was then sealed and left to stand in a cool room at 10 C/ 50 F.

The first samples to be tested were those marinated in Sake (Rice wine) for a period of 4/5 days. The attached images show that both samples were

successfully clamped to the profile of the mold after boiling. The Maple sample cracked at both ends - the cracks running for 25 mm and 15mm in length

respectively. I am not too concerned about the end cracking - which is due to intensified tensile stress at the free ends of the sample, stresses most

likely further amplified by the rough, sawn, edges - the saw cuts being 'stress raisers' or local points of high stress concentration. This fault may

be minimised in future full scale tests by ensuring that the ends of the rib blanks are cut smooth and by leaving extra length to the blank so that

such faults may be cut off.

jdowning - 11-17-2008 at 01:39 PM

So far so good. The walnut sample after release from the mold retained the desired inverted saddle shape. The dried, bent sample measures about 1.1 mm

thick. The longitudinal radius has 'sprung' on drying from a radius of 27 inches to 34 inches (686 mm to 854 mm) and the flute inside radius is

maintained at 18 mm.

The thicker Maple sample at 1.3 mm thick also achieved a longitudinal radius of 34 inches but the inside radius of the flute opened up to 24 mm (about

15/16 inch). Not quite so good.

There are a few variables to take into account here, but thinner would seem to be better as far as three dimensional bending of the samples is

concerned - less tensile stress in bending.

Wow

Clayton - 11-17-2008 at 08:33 PM

Hi jdowning,

Just want to say a few words... about what interesting work you are doing.

I have not seen how it can be done to curve the wood on two axis, however, it must be possible because I have seen the resulting instruments and it

must be a relatively simple set up and process because it was done in shops in the 16-17th century... before sophisticated steam bending machines

etc... I have seen furniture done this way as well... fluted chair backs and fluted chest tops etc... Keep up the good work and good luck with your

progress.

Do you make or play lutes? I think I read one of your posts that mentioned that.

jdowning - 11-18-2008 at 04:45 AM

Thanks Clayton - we should be careful not to underestimate the technical skills of the luthiers (and other craftsmen/tradesmen) of the 16th C and

earlier. I suspect that more useful technology has been lost forever in the course of history - gone to the grave with the practitioners - than we

have remaining available to us today. The challenge is to try to rediscover what has been lost by a process of experimentation using materials and

methods that would have been available to those early craftsmen.

I don't believe that steaming the wood is the answer in this case - and I have no doubt that steam bending of wood (at atmospheric pressure) was a

technology practiced in earlier times. I believe that a simpler process was used - but not because steaming technology was not available.

I have been immersed in early music interests for over 30 years, both as a maker and player of early instruments, having made several lutes, vihuelas,

guitars etc. during that period - for my own use and research purposes. (see 'Old Project - New Lute' on this forum for example). However, I have many

other interests as well, particularly in the field of early technologies - but that's another story!

Josh - 11-18-2008 at 05:22 AM

it seems to me that some kind of pee is usually involved when making anything medieval

patheslip - 11-18-2008 at 09:29 AM

Josh is right, urea is used to soften lignin

jdowning - 11-18-2008 at 12:24 PM

Yes, it is used for chemical wood bending but apparently is not as effective as steam bending - and it is a component of urine.

Urine had an application in the past as a chemical used in dyeing wool and yarns - even for dyeing hair among some 'primitive' peoples. It was used

either fresh or fermented (i.e. 'stale'when the urea component converts to ammonia). I did give some thought to adding it to my list of marinades but

decided against it - for now at least. Besides determining the best urine for the job and from which animal would likely be a big investigation in

itself. It has the benefit of being much safer than some of the chemicals that I am already testing.

When checking out the urea question, I came across a traditional method for softening Coir fibre - fibre from coconut husks. The husks are 'ponded' -

immersed in ponds of brackish water for up to 12 months for anaerobic bacterial activity to do its work after which time the fibres become soft and

pliable. Sound familiar? As I now recall "retting" is (was) a process also used in preparing flax fibres for weaving.

The challenge would be to ensure that the bacterial action did not go so far as to significantly weaken the fibres of wood in our case. The 'ancients'

had plenty of time to figure it all out - I don't!

jdowning - 11-18-2008 at 01:29 PM

I forgot to mention that during the failed boiling test - i.e. without any marinating - the Walnut test piece curved in cross section on removal from

the boiling water.

I had to cut this test piece from a different batch of Walnut - this time with the grain running at about 15 to 20 degrees from the horizontal i.e. a

partial slab cut rather than quarter sawn - so this may be another indication that slab cut rib blanks may perform best.

I now have the results of the stage 1 bending tests after pre-soak. I shall just summarise the results but if there are any questions I can provide

more details. The samples, marinating fluids and pre-soak time were as follows :-

#1 Walnut - Sake - 4 days.

#2 Maple - Sake - 5 days

#3 Walnut - Beano in Water - 6 days

#4 Maple - Beano in Water - 7 days

#5 Maple - White Wine - 9 days

#6 Maple - White Vinegar - 10 days

#7 Walnut - Wood Alcohol/Ammonia Solution - 10 days

#8 Maple - Wood Alcohol/Ammonia Solution - 11 Days

The Beano and Alcohol/Ammonia fluids became discoloured - Beano blue and the other purple so something was going on there.

All of the samples were bent successfully - after boiling - to the required shape but with various degrees of 'spring back' following release from

the mold and further drying. Minor end cracking occurred in samples #2,3, and 6. The Walnut samples were all easier to bend than the Maple samples.

Spring back varied in the Walnut samples, from the original longitudinal mold radius of 27 inches - 27 inches up 34 inches and from the original

flute radius in cross section of 18 mm inside - 18 mm to 20 mm and for the Maple samples - longitudinal radius from 30 inches to 35 inches and flute

inside radius from 20 mm to 24 mm.

The most successful tests were samples #7 and 8 the Walnut maintaining the exact mold profile with thickness 1.02 mm and the Maple opening up to a

longitudinal radius of 30 inches and flute radius of 20 mm with thickness 1.5 mm.

The thickness of the samples varied from between 1.02 to1.15 mm for Walnut to 1.3 to 1.7 mm for Maple. The walnut sample #7 was so flexible after

marinating that it could be cold formed into the mold contours without need for boiling.

Clearly there a number of variables here that may affect the end results - pre-soak time (longer is better), thickness (thinner is better), material

(open grain wood easier to marinate than close grain wood). Also the test mold being less than half the length of the full sized 'Dias' mold, there

will be a greater length of longitudinal bend and hence increased tensile stress to accommodate when it comes to full size testing. So, satisfactory

result but a way to go yet.

Having put "the cart before the horse" by not first testing with plain water or ammonia and wood alcohol separately as marinating fluids, Walnut test

samples are now being pre-soaked in these fluids for part 2 of the tests. Sample thickness is 1.1 mm. I have also include a repeat of the Sake and

Beano pre-soak because I want to test the effect of a much longer pre-soak time on all of the samples - say a month. The Walnut samples are all

partially slab cut with grain running at 15 to 20 degrees to the horizontal.

As I still have most of the Sake left - decided to do another taste test - just to make sure that it had not gone sour you will understand. Not too

bad actually. Cheers!

jdowning - 11-19-2008 at 07:57 AM

I have added a 50/50 wood alcohol/ glycerine mix to the list of marinades to be tested during this second phase about a month from now. I am beginning

to suspect that pretty well any moisturising fluid that can be soaked into the wood to reconstitute the dried out cell matter will have some softening

effect.

The attached image shows the test pieces from phase 1 of this experiment - all successfully bent longitudinally as well as in cross section. The image

of the edge of Maple test piece #8 shows one disadvantage of using string as a clamping device. String cuts into and damages the edges of the softened

wood. It does illustrate how soft the wood had become in this case however. To overcome this problem use of strong fabric tape would distribute the

pressure more evenly and would also better support the outer surfaces of a piece against failure due to tensile stress in bending.

An improvement in mold design might be to construct it from guided articulated segments. This way the bending would be accomplished in two stages -

the first to bend the flute curve with the mold segments laid straight and the rib blank strapped to the mold segments with fabric tape, the second

step being to then immediately force the mold, with rib blank in position, into the required curve. Food for thought at this stage.

patheslip - 11-19-2008 at 09:15 AM

On the urine question, the Romans had large jars on town crossroads to collect wee for tanning leather. Don't be shy now.

Seriously, this is a most interesting investigation. Keep up the good work.

Josh - 11-19-2008 at 09:34 AM

maybe it was boiling pee.. eek

jdowning - 11-19-2008 at 02:24 PM

Yea, well when you live in rural farming areas, as I do, you get used to this sort of thing!

The Scots, like the Romans also had communal collecting pots that they would contribute to on their erratic journey home after consuming a few 'malts'

during the course of an evening. Perhaps the liquid intake makes a difference to the final product?

As for the products used for tanning leather by the ancients, urine is only the first step. What follows in the process - although very effective -

gave the leather tanning industry an unpopular reputation in polite society and cast it to the nether regions outside of town and city boundaries -

and banished the employees of this essential industry to pariah status . I won't say what it was but suffice to say I do not intend to go that route

and join the numbers of the great unwashed in modern society - even in the interests of science or whatever!

Today I looked again at the notes that came with the museum drawing of the Dias guitar made by London luthier Stephen Barber.

Barber is convinced that the ribs are made from Kingwood (Dalbergia cearensis) - a member of the rosewood family very similar to Brazilian rosewood

but which, he says, is more elastic and easier to bend than the latter. He informs us that Kingwood comes from a tree of small dimension - 15 to 18 cm

in diameter (6 to 7 inches). This would have been the size of timber generally available to luthiers of the late 16th C with connections to the 'New

World".

The small log size of this timber implies that at least partial slab cut sections of rib stock may have been used?

I have chosen Black Walnut for continuation of these trials because I have some in stock and because it has proven in stage 1 to be easier to bend -

and quicker tp prepare - than Maple (we must learn to crawl before we can walk).

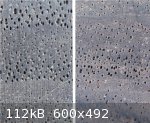

Also, Black Walnut has a similar open cell structure to the true Rosewood genus (see attached macro images Walnut to left - Indian Rosewood to right,

made from samples that I have in stock) - not that the woods are equivalent - but the similar open cell structure should allow for better absorption

of softening fluids for both types of wood? I also have some Brazilian Rosewood lute pegs (made from larger billets purchased in the 1970's) so will

macro photo the grain structure of those for comparison.

jdowning - 11-20-2008 at 01:08 PM

For comparison - here is a macro image of one of the lute pegs, mentioned in the previous post, made from Brazilian Rosewood (Jacaranda), Dalbergia

nigra. I should still have the 'off cuts' left over from the peg turning operation - from which I could make images covering a wider area - but I

cannot find them. A better set up for making the macro images needs to be made - with a reference scale to aid comparison - but I haven't got around

to it yet. The diameter of the end of the lute peg is

6 mm. Note that the macro images have to be compressed (reduced in size) for efficient posting on the forum which results in a significant loss of

definition, or clarity, compared to the original images.

The cell size and distribution of Jacaranda is quite similar to another species of rosewood that I have to hand - Cocobolo (or Grenadillo), Dalbergia

retusa.

As Indian Rosewood, Dalbergia latifolia (at least as far as these samples are concerned) seems to have a greater proportion of randomly distributed,

large diameter cells than either Jacaranda or Cocobolo I would guess that it would be quicker to soften and easier to bend - but that is just a theory

at this point in time, yet to be tested.

Note that all of the rosewoods have material - resin and mineral deposits etc. - packed within a proportion of the cells (visible in the macro images)

that may be supporting the cell walls against distortion under compressive loads (experienced during bending). These are 'extractives', which, if they

can be dissolved and removed by the pre-soak marinade fluid - might render the wood more pliable? Just a theory yet to be tested

Once the best marinade and soak time has been determined experimentally for the 'easy' wood - Black Walnut - Indian Rosewood will be next in line for

testing.

Clayton - 11-21-2008 at 12:06 AM

What an great investigation...

I encourage you to continue to both explore the practical methods and to keep us informed of your progress!

I am engrossed!

on a note... not more than obliquely related...

I was told:

...that if you add urea to hide glue, you get a room temperature hide glue... just food for thought and grounds for further research!

jdowning - 11-22-2008 at 07:31 AM

I hadn't realised before that urea was used to make liquid hide glue or that liquid hide glue was as popular among woodworkers as it seems to be these

days. I made the mistake many years ago of purchasing a half gallon tub of prepared liquid hide glue. As I recall, this stuff was of a rubbery

consistency so still had to be heated before use so I suppose was a bit more convenient to use than glue granules. Anyway, by the time I got around to

using it, the whole lot had decomposed so was useless. Just as well, I suppose, as it is not recommended to use liquid hide glue for instrument

making.

Urea, in white powder form, it seems, is readily available for use as a fertilizer from gardening stores so would be a convenient way to make up into

a marinade. Not sure if the locals will stock it this time of year so that will have to wait until Spring next year.

While phase 2 samples are being marinated, here for information and comparison is a macro of the cell structure of the Cocobolo that I have in stock.

Very similar in structure to Brazilian Rosewood.

jdowning - 11-22-2008 at 07:45 AM

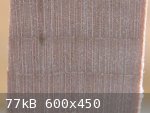

..... and, to complete the picture here for comparison is a macro of the cell structure of the maple used in these trials. Unfortunately a reference

scale was not used to enable direct comparison but it can be seen that the maple has smaller cells so absorption of the marinating fluid may be a lot

slower than it might be in wood species with larger cells.

jdowning - 12-7-2008 at 05:00 PM

Winter has arrived in this part of the world about a month earlier than usual so plans have had to be modified accordingly as temperatures drop

considerably. The phase 2 samples, marinating since 18 November have, therefore, been moved into a warmer location (the kitchen - heated with a wood

stove) so that any bacterial action of the marinades may continue and develop.

Progress was checked today. The phase 2 marinades, with walnut test samples, are:

- Water

- Sake

- Beano

- Household Ammonia solution

- Wood Alcohol.

- 50/50 Glycerine/Wood Alcohol

The Wood Alcohol bag was found to be empty, having leaked, and the sample dry. The sample was, therefore, transferred to a sturdier polythene sealed

box to re-soak.

The fluid in the other sealed bags all showed some colouration indicating that some kind of chemical/bacterial action was in progress. The most

significant colour change is noted in the Beano and Ammonia marinades (with Wood Alcohol at present unknown) - the fluids having a deep brown

colouration.

The depth of colour of the marinade may be useful in future as a guide to judge optimum time of immersion.

At the same time, the phase 1 samples were checked dimensionally to determine their stability after initial drying after bending. Samples #1 to #6

showed a measured increase in longitudinal radius of 12% to 18 % with no significant change in the radius of the fluting. Sample #7 showed no change

in either dimension so is considered stable. Sample #8 showed a 7 % increase in longitudinal radius. The stable dimensions of sample #7 may be due

either to the marinating fluid or immersion period (which was longer than for the other test samples) or to the wood species (Walnut versus Maple).

The phase 2 samples will be tested for bending in about a week i.e. after about a month marinating.

jdowning - 12-15-2008 at 11:29 AM

Phase 2 bending started today, the samples having marinated for about a month.

Sample #9 Walnut in Sake - marinated for 28 days. The marinating fluid had a light brown tinge to it and the sample was quite flexible when cold. It

had curved slightly across its width and - in the same direction - along its length. The sample was boiled in water for 5 minutes and then tied to the

mold as for the Phase 1 samples. The sample was placed on the mold with the curvature across its width following the curvature of the mold (i.e. the

curve of the fluting).

The sample split at both ends as it was being tied to the mold - the most severe of the splits being 4 cm (1- 5/8 inches) long.

So this is considered to be a failure unlike sample #1 (walnut in sake, phase 1 tests) that bent without splitting after only 4 days marinating.

Sample #1 is quarter sawn, sample #9 is part slab sawn which might be part of the problem

For Phase 2 tests, I am using an elastic (stretchy) fabric tape (ice hockey boot laces - cheap, strong, wide and long) instead of string which cuts

into the softened wood. The wide tape distributes the pressure more uniformly so should reduce the tendency of a sample to split. Not in this case,

however!

The sample will be left overnight to dry and sample #10 will be bent tomorrow - hopefully with better results.

jdowning - 12-16-2008 at 11:44 AM

Sample #10 - Walnut in Beano, marinating 29 days. Marinating fluid dark brown. Sample coated with a slime.

After boiling in fresh water for 5 minutes the sample was tied to the mold. It cracked at one end - crack 3mm long.

jdowning - 12-17-2008 at 12:27 PM

Sample #11 Walnut in plain water - marinated for 30 days. There was bacterial growth in the fluid and a slime on the surface of the sample. The fluid

was tinged a medium brown colour.

After boiling for 5 minutes, the sample was tied to the mold. It cracked at the ends like sample #9 and #10. The cracking of sample #9 is shown in the

attached image - similar to sample #10 after air drying for 24 hours.

A close inspection of sample #10 indicated that the cracks are being initiated in the late wood cells exposed on the surfaces of each sample. It can

be seen that - as there is very little 'run out' of the longitudinal grain in the Phase 2 samples - the open cell structures exposed at the surfaces

of the samples are relatively long and so constitute a weakness causing localised thinning of the sample as well as acting as stress raisers. The

exposed latewood cells appear in parallel groups on the surface because the samples are slab cut. Slab cut wood is also stiffer across the width of a

sample so may be more difficult to bend into a fluted section.

Contrast this with sample #7 from the Phase 1 tests - successfully bent without cracking. It so happens that the longitudinal run out of the Phase 1

samples is about 5 - 10 degrees so that the exposed cell structures are much shorter and more random in distribution. Also, these samples, being

quarter sawn, can flex more readily across the width of a sample so should be easier to bend into a fluted section.

It is anticipated that the remainder of the phase 2 samples will also crack when bent for the above reasons - but time will tell.

Longitudinal grain run out may turn out to be an important factor in order to successfully bend fluted ribs.

jdowning - 12-20-2008 at 12:57 PM

Sample #12 Walnut/50% glycerine- 50% alcohol marinade. Soaking for 31 days. Fluid tinged pale brown.

The sample cracked at one end during bending - length of crack is 3 cm (1.2 inches).

The attached image is the end grain of sample #12 after 24 hours air drying. The measured thickness is 0.94 mm (0.037 inch) so there may have been

some reduction in thickness prior to marinating of around 15%. The camera was hand held (not recommended for macro photos!) but the image is clear

enough and illustrates the problem with all of the Phase 2 test samples. It can be seen that the early-wood cells are of significant diameter compared

to the thickness of the sample (looking like Swiss cheese - or worm eaten wood!). As there is no longitudinal grain 'run out' in the Phase 2 samples,

the exposed cells, on both sides of the sample, are quite long, creating a weakness and points of high stress when subject to bending under tension-

equivalent to scoring the samples with a knife.

Sample #13 Walnut/Household Ammonia solution. Soaking for 32 days. The marinade fluid was a deep mahogany brown. The sample was very pliable and after

boiling for 5 minutes was tied to the mold without cracking. This is an encouraging result - particularly in view of the problem with Phase 2 samples

(although the sample may still crack after air drying for 24 hours). An ammonia solution in water of 5% to 10% is not supposed to be effective in

softening wood (unlike liquid ammonia) but both Phase 1 and Phase 2 tests involving household ammonia have both produced promising results so far.

The last test in Phase 2 will be Walnut/Wood Alcohol.

jdowning - 12-21-2008 at 12:57 PM

Sample #13 has been released from the mold after air drying at a room temperature of 65 F (18 C) and relative humidity of 50% for 24 hours. The sample

has not cracked. However it had shrunk and distorted significantly (shriveled) as can be seen in the attached image where the sample is shown along

side sample #11 for comparison. Compared to sample #11, maximum shrinkage across the width of the sample (measured in the middle) is about 20% but

there is no measurable shrinkage in the length. The Ammonia solution has softened the cell walls of the wood to the point where they have shrunk in

size during drying. The ends of the sample that were not restrained by the binding tape have become 'bell shaped'.

Had the sample been quarter sawn, it is expected that the degree of shrinkage and distortion would have been less.

So - no matter what the experts say - a 5% to 10% solution of Ammonia in water will work in softening the cell wall - like liquid Ammonia does - it

just needs more time. Liquid Ammonia presumably softens the wood very quickly - so is commercially more viable. No doubt if wood is left in liquid

Ammonia for an extended period, it would also suffer the same degree of shrinkage and distortion? Clearly, in this test, the marinating time has been

excessive (so the results are a failure as far as bending is concerned) but it does demonstrate the softening power of Ammonia. Shorter marinating

times and/or a more dilute Ammonia solution would likely be more successful. More testing is required in order to find the optimum set of conditions

for bending using a dilute Ammonia solution.

Sample #14 Walnut in Wood Alcohol. This sample has been marinating for the same period as the other samples in

Phase 2 but - due to a leaking Ziploc bag - was found to have dried out when inspected on the 7th Dec. Since then the sample has been re-marinating in

a fresh solution of wood alcohol but it is now difficult to know if the marinating period should count as 14 days or 33 days. Nevertheless, it was

decided to go ahead with bending the sample. After boiling in water for 5 minutes, the sample was tied to the mold without cracking and left to dry

for 24 hours.

Another promising result!

jdowning - 12-22-2008 at 12:18 PM

Sample #14 cracked at both ends after drying for 24 hours with one crack measuring 2 cm long and the other 1 cm. Nevertheless, this is a positive

result as allowance can be made to trim a rib after bending.

The attached image shows a cross section of sample #13 (cut in the middle of the sample) compared to sample #11 to illustrate the degree of shrinkage

after marinating in the Ammonia solution. Note that the radius of the fluting is also reduced.

jdowning - 12-22-2008 at 12:37 PM

The attached image shows the cell structure of sample #13 (at the mid section) after marinating in Ammonia and drying compared to sample #12 end

grain. It can be seen that the larger diameter early wood cells have been reduced in size after drying and the structure of the wood has become

compressed and more compact.

Had the sample been quarter sawn there would have been less reduction in the width of the sample but a greater reduction in thickness. This will be

worth another test as, after Ammonia treatment, wood becomes quite plastic in nature so should have the advantage of allowing greater scope for more

extreme bending of the wood - perhaps without the need for heat.

jdowning - 12-27-2008 at 12:17 PM

At this stage it might be worth briefly summarising the overall results from the Phase 1 and Phase 2 trials.

All of the marinating fluids provided a degree of softening of the samples allowing them to conform - some better than others - to the mold curvature.

However, the most successful result was sample #7 Black Walnut marinated for 10 days in a 50/50 mixture of household Ammonia solution and Wood Alcohol

(Methanol). This sample retained the transverse and longitudinal curvatures of the mold when released after drying on the mold for 24 hours. Measuring

the sample again today - since 15th November - the longitudinal curvature is unchanged at 69 cm (27 inch) radius but the radius of the fluting has

decreased slightly to less than 18 mm radius (i.e. it is more fluted). The thickness is unchanged at about 1.02 mm. There are no visible cracks. The

sample is therefore judged to be stable

The Phase 2 trial with Walnut sample #13 marinating for 32 days in Household Ammonia demonstrated that even a dilute solution of Ammonia in water does

have a significant plasticising effect on wood. In the case of sample #13 although the sample shrank during drying and the cell structure became

compressed under the bending stresses, the sample did lose its plasticity and become hard again on drying.

The 50/50 blend of Ammonia/Methanol was just a guess but it may be that the alcohol was only a diluting agent for the Ammonia and that water might

have done just as well in place of Methanol. It is possible that by using Ammonia solution as a marinating fluid (under optimum conditions yet to be

determined) that ribs might be bent without use of heat - and also conform to the more extreme curvatures required of oud or lute fluted ribs.

Samples of Maple were more difficult to bend than Walnut possibly because the Walnut has larger, thin walled, early wood cells than maple so the

marinating fluids can act in softening the wood more quickly. However, it is likely only a matter of adjusting the marinating period to allow woos

species with small cells more time to soften - or to adjust the strength of the marinating fluid - or a combination of both.

The grain direction of the wood seems to be important for successful bending. The walnut samples in Phase 1 were quarter sawn (end grain running

vertically) and with a longitudinal grain 'run out' of about 5 degrees. The quarter sawn grain provides the greatest degree of transverse flexibility

and the short longitudinal grain reduces the stiffness in that direction both factors allowing easier compound bending. Presumably the greater the

degree of longitudinal grain run out the greater the degree of flexibility but this would have to be tested to confirm. The reduced stiffness of the

unbent rib blanks should not be a problem as the fluted ribs in the finished instrument would not only be thin and light but very stiff by virtue of

their geometry.

So where to go from here? Phase 3 trials will now focus on Household Ammonia solution as the most promising marinating fluid to try to establish the

optimum fluid concentrations and marinating periods for a selection of woods - including tropical hardwoods - using the original mold and sample

dimensions of Phase 1 and 2.

Phase 4 trials will be to test bend full length ribs for a Dias guitar.

Phase 5 trials will be to attempt to bend fluted oud or lute ribs - probably with the rib blanks in a fully plasticised condition. Phase 4 an 5 trials

will require a new male mold for the Dias ribs as well as a sealed chamber of the required length to hold the longer blanks while marinating.

This will all take some time to complete but I am now more optimistic in being able to succeed in this investigation - certainly with the guitar ribs

but also, possibly, with the more challenging oud ribs.

jdowning - 1-7-2009 at 11:15 AM

For those who might be interested, here are three scientific papers about wood degradation caused by bacterial and other action - as found in wood

taken from archaeological sites in Ancient Egypt, Turkey and elsewhere.

Hopefully short term bacterial action - deliberately employed to temporarily soften the cell structure of wood - will be less destructive than in

those woods exposed for thousands of years. This would, presumably, depend upon the bacteria being destroyed and the conditions required for bacteria

to thrive being removed - as should be the case for dry, seasoned woods used in musical instruments.

http://aic.stanford.edu/jaic/articles/jaic33-01-005.html

http://forestpathology.cfans.umn.edu/pdf/IBBreview2000.pdf

http://www.pnas.org/content/98/23/13346.full.pdf+html

jdowning - 1-10-2009 at 01:14 PM

In order to establish the length of time it takes for Household Ammonia solution to plasticise wood, Walnut samples are to be subject to yield

testing. The marinating fluids will be Household Ammonia - undiluted; 50% Ammonia solution/ 50% water; 50% Ammonia solution/ 50% Wood Alcohol.

The marinated samples will be tested every 24 hours by clamping each sample in a test rig, applying a standard, fixed load to the end of each sample

and measuring the deflection at the load point on the sample. The attached images show the rig set up.

Samples in an untreated, (i.e. unsoftened) state will retain their elasticity under the (briefly applied) test loading - that is when the load is

removed the sample will spring back to its original position on the rig. At some point in time, however, the sample is expected to soften and so will

lose its elasticity - i.e. it will not return to its original unloaded position on the rig. This will be the initial yield point of the sample and

will be an indication of how long a sample must be marinated to become plasticised. At least, that is how I see the test working so we will see how it

goes.

Also, in order to get a better idea of what happens to the cell structures of different wood species when plasticised by Ammonia, several test samples

- cubes measuring about 12mm (0.5 inches) on each side - have been left to soak in Household Ammonia solution for 30 days in a sealed jar. The wood

samples are Vine, White Ash, Black Ash, White Elm, Black Walnut, Beech, and Indian Rosewood.

There was an immediate action noted on adding the Ammonia solution - the fluid quickly becoming a dark brown colour. So something is definitely going

on there. After 30 days the samples will be boiled in fresh water for 10 minutes and the softened end grain sliced with a razor in preparation for

taking digital micro images of the cell structures after drying.

jdowning - 1-15-2009 at 01:31 PM

The Walnut test samples for the yield test have been marinating for 5 days (120 hrs) and have been tested daily. Each sample has been loaded with a

constant load and the deflection at the end of the sample measured with calipers. This method of measurement, in retrospect, is not very satisfactory

but gives a rough idea of the softening effect of the marinating fluid with time.

The Ziploc bag containing the Ammonia solution marinade has started to leak so, today the sample has been transferred to a new bag with fresh marinade

so this is not a set back.

Preliminary observations.

The test samples in the Ammonia solution and Ammonia solution diluted 50% with water have shown the greatest increase in plasticity with increased

deflections under constant load of about 115 % over 120 hours. This compares with an increase of about 25% for the sample marinated in the

Ammonia/Wood Alcohol solution. Clearly, the wood alcohol has a moderating effect and the test sample does not show the same distortion (buckling and

twisting) as the other two test samples.

It is estimated that the first two samples are close to their yield points i.e. being fully plasticised.

The tests continue.

jdowning - 1-21-2009 at 01:08 PM

The wood samples - cubes measuring 0.5 inch (13 mm) on all sides - have been marinating in Ammonia solution in a sealed jar for 10 days after which

time they were removed for examination. Each sample was boiled in water for about 5 minutes and allowed to dry. The duration of the test was reduced

as the softening effect of the Ammonia solution appears to be much more rapid than previously thought.

After drying, each sample was observed to have shrunk to a degree - shrinkage being greater along the growth rings than radially across the rings as

it would be if the wood had been dried in the usual manner from being freshly cut. The least amount of shrinkage was found in the sample of Indian

Rosewood (closely followed by American Elm) and the greatest amount in a sample of White Ash.

Images of the cell structures of each sample - before and after marinating - will be posted separately for information.

jdowning - 1-22-2009 at 10:19 AM

The most dramatic example of wood shrinkage after marinating in Ammonia solution is seen in the sample of White Ash. The sample, after drying is now